Homesteading the Memeosphere

Seong-Young HerEric S. Raymond, in “Homesteading the Noosphere” (1998):

Nothing prevents half a dozen different people from taking any given open-source product (such as, say the Free Software Foundations’s gcc C compiler), duplicating the sources, running off with them in different evolutionary directions, but all claiming to be the product.

In practice, however, such ‘forking’ almost never happens. Splits in major projects have been rare, and always accompanied by re-labeling and a large volume of public self-justification.

[…] What does ‘ownership’ mean when property is infinitely reproducible, highly malleable, and the surrounding culture has neither coercive power relationships nor material scarcity economics?

[…] What we see implied in hacker ownership customs is a Lockean theory of property rights in one subset of the noosphere, the space of all programs. Hence ‘homesteading the noosphere’, which is what every founder of a new open-source project does.

[…] [Hacker culture is] a ‘gift culture’ in which participants compete for prestige by giving time, energy, and creativity away.

The reason that memepages were such a revolutionary force was, in part, because they could accumulate reputation and following for individual shitposters. But reputation per se still plays a role even in anonymous environments. On 4chan, the platform (or subfora such as /b/) accumulated the reputation instead of the individual users. Not only that, but as anyone who has used an imageboard quickly comes to realise, you can often tell (intuitively, based on things like tone and content) if you’re interacting with the same poster.

Going further back than imageboard culture, the “hacker ownership” of memes can be seen at work, such as in memes like “Godwin’s Law” (1990) and its corollaries such as “Miller’s Paradox” or “Gordon’s Restatement of Newman’s Corollary to Godwin’s Law”. This mode of thinking about memes as something individuals can invent (and put their name on) was superseded alongside enthusiasm for memetic engineering, replaced by hostility against forced memes; it has since been revived with the maturation of ironic memes and memepages.

It’s intriguing to me that, just as with the “Promiscuous Theory, Puritan Practice” that ESR talks about, memers adopted and utilised contradictory theory and practice in response to different platforms. Namely, the notion that memes are organic, genic, or viral, paired with the notion that memes can be engineered; the notion that memes are cultural products made by individuals or communities, paired with notion that memes emerge naturally and cannot be forced (or at least a taboo against such behaviour).

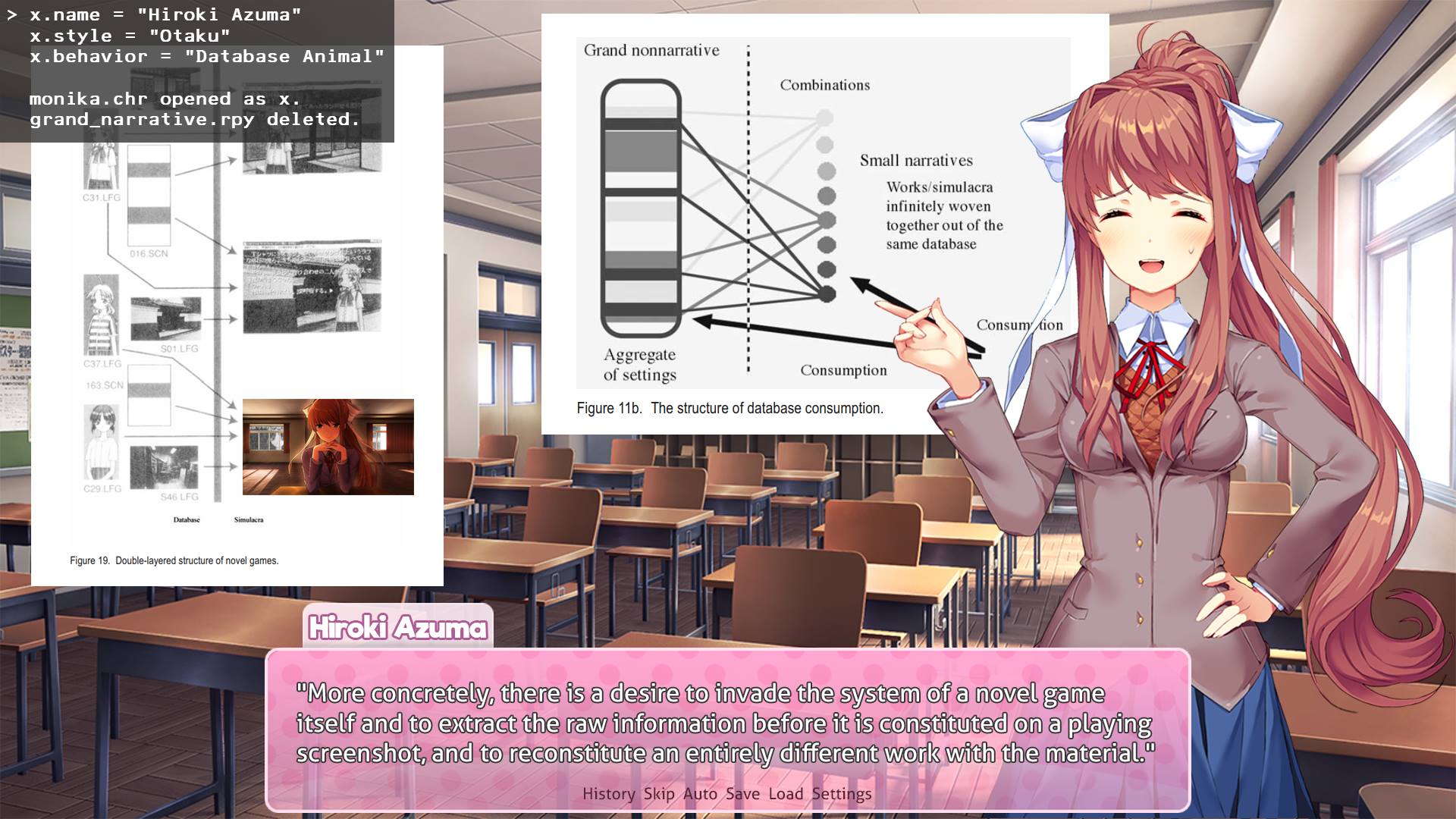

Compare this with Azuma Hiroki’s argument that otaku economies consume metanarratives (rather than grand narratives, which are dead) which are constructed ad hoc based on a database of narrative materials provided by original works that instigate the subcultures. For instance, the anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion provides the database of characters, world building, concepts, and so on; otakus can draw upon this database in order to produce fan fiction and fan art, which often deviate wildly from the original anime. In Azuma’s model, otakus do not consume the work itself but rather the database which lays behind the work (both canonical and unofficial). Otaku culture involves puritan theory and promiscuous practice. In theory, all unofficial material is secondary to the canonical works. In practice, fan-made (or even canon-contradicting mediamix) is nonetheless welcomed and consumed.

Meme by Material Memes and Dialectical Dreams (2018).

The concepts of property and ownership are intuitively, if not necessarily, tied to the concept of owners and boundaries. Ownership is a relationship between property and its owner bounded by some custom or agreement, be it norms or law. The question of “who owns the meme?” is a discomforting one for those who love and appreciate memes and memecultures, partly because the continued lack of common agreement seems to be a foundation for much of contemporary memecultures. The rejection of the very question has often served to postpone individual ownership of unowned or commonly-owned objects; radical responses, adamantly asserted, have often served to mask the fact that the question had been rejected without consideration. If the very question of what memes are remain taboo, then so too would questions of boundaries around memes (which enable the question of ownership), and so on.

Nevertheless, there are hidden assumptions of ownership and property within meme culture that come to the fore in unexpected, sometimes dangerous ways: memepages engaging in mass report wars to have each other taken down; stock image businesses copystriking memers for using their photos in a meme; memers turning memes into NFTs. If the philosophical question of ownership had been considered more exoterically by memers, would these kinds of threats to meme culture have been prevented? It’s hard to say. Esotericism served it well enough for a long time, and that kind of strategy is not unique to meme culture, precisely because it’s effective. But the larger a subculture becomes, the less effective esotericism becomes as a defence against cooptation. That’s why esotericism typically attacks not only what it considers the threat of entryism, but the careless, rapid expansion of the ingroup.

The memecultural esotericist taboo discourages being exoteric about your love for memes and meme culture, perhaps because “it’s cringe” or because it ostensibly “will ruin them”. This taboo is not only nonsensical, but dangerous too. It’s too late for this kind of esotericism. The concept of memes as popular cultural products are now mainstream without a shred of doubt, but memecultures still vary wildly. That diversity is a good thing; the received wisdom of subcultural esotericism going unchecked is not. Without more memeculturalists themselves “stooping to the level of normies” and earnestly engaging with the philosophy of memes, the work of defining memes and meme culture will be left to outsiders.

I think that many memes have great value and significance, historically and culturally, as well as intrinsically, but only when they are healthy and alive. A meme folder is dead without the rest of the memetic ecosystem to express it. The outgroup-first perspectives provided by outsiders to memecultures will prioritise what makes all memecultures the same. It will focus on aspects that affect outsiders the most, namely money and politics, and pick out readily accessible parts of memecultures that can be conveniently archived and cited as exemplar specimen.

Conceptualising memes monoculturally and excluding the ingroup-first, emic perspectives that respect the importance of cultural context (such as by focusing solely on memers and their audiences, or solely on memetic artefacts such as posts or images), will pave the way to a thorough commercialisation of memes and memecultures. Memeculturalists will then have no choice but to adopt the definition of meme culture provided by people who never had a stake in the culture itself.

Hilary Putnam said: “The problem with just giving up on philosophy is: bad philosophy is omnipresent. […] if professional philosophers gave up talking about philosophy, your novelists wouldn’t; your physicists wouldn’t; your biologists wouldn’t; your self-promoted god-knows-what wouldn’t. We’d be deluged in nonsense. We will be deluged in nonsense, but at least there has to be some, still small, voices, like the boy saying the emperor has no clothes, saying that’s nonsense.”

We are already deluged in nonsense about memes, and I treasure the (still small) voices that speak up for the memes.