What Is A Meme?

Claudia VulliamyAbout the author: Claudia Vulliamy recently graduated in Philosophy at the University of Bristol, where she specialised in aesthetics. She is also a musician in the dream-pop band Oslo Twins.

Introduction

Internet memes, an increasingly popular phenomenon, are normally images that spread online. They are continuously shared and altered by internet users to form communal running jokes. Having first emerged in the 2000s and drastically changed in style over time, the digital nuggets of humour are now an inescapable part of youth culture. Although the first instances were basic, universally appealing pieces of online comedy, memes have become a unique artistic medium in which complex cultural experiences are conveyed through both form and content, layered with irony and intertextuality. Similar to the issue of defining art, identifying the essential properties of memes has become more challenging as memes have become more avant-garde. In my attempt to answer the question ‘What is a meme?’, I will focus primarily on Simon J Evnine’s paper Anonymity Of A Murmur[1]. I will critique Evnine’s definitions and argue that his conceptual definition of a meme over generates, allowing things to be called memes that should not be. I will then argue that a meme, like art, is a fuzzy concept and should be defined in a way that accounts for that. My descriptive account of memes bears similarities to a ‘cluster’ definition of art. I will analyse what I view to be the core properties of memes: memographic practice, comedy, public shareability, use of images and/or text, digitality, appropriation, anonymity, ephemerality and stylistic resemblance to other memes.

There has been, so far, very little written on the subject that is specifically definition- focussed, so most of my sources for this paper have been personal research among my peers, from which I have gained insights into the varying ways in which people hold the concept of a meme.

Terminology

Firstly, I will make it clear that I am not referring to memes in the sense used by Richard Dawkins. Dawkins’ use of the word ‘meme’ is the etymological origin of the internet meme, since it describes an element of culture that spreads from person to person via imitation and mutates over time [2]. But although internet memes can be seen as a sub-category of Dawkinsian memes, these are distinct concepts and I do not see Dawkins’ use of the term as useful in defining internet memes. Many theorists on internet memes (such as Shifman [3] and Milner [4]) have, more or less, taken the concept ‘internet meme’ to include almost any Dawkinsian meme that spreads via the internet. However, I will focus on the concept of an internet meme that is used most commonly among young internet users and meme enthusiasts today - something more specific than what these theorists are describing and something which Evnine attempts to define. This is a concept that does not include, for example, a viral music video, but does include each of the following images, which are variations on the same meme-trend [5].

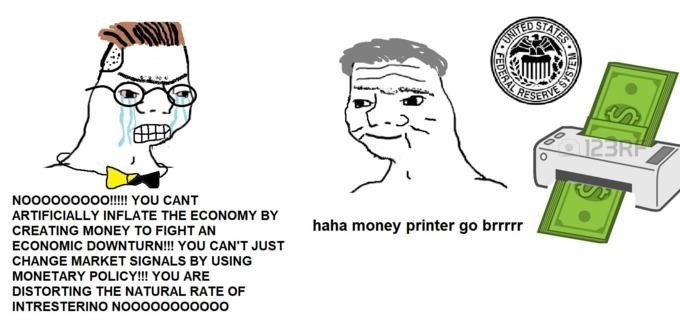

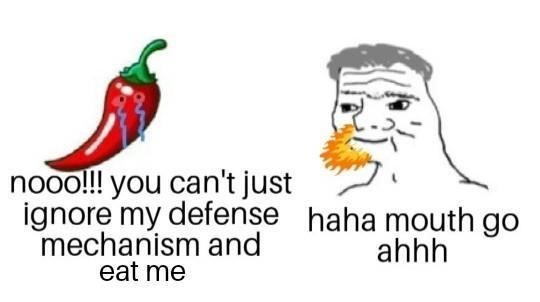

Figure 1: ‘Money Printer Go Brrr’, an image macro depicting two drawn figures (variations of the ‘Wojak’ figure) representing the US Federal Reserve’s attempt to prevent economic downturn. Source: Know Your Meme

Figure 2: One of the variations upon the ‘Money Printer Go Brrr’ meme format. Source: Know Your Meme

Secondly, to distinguish this idea from Dawkins’, I have so far referred to these things as internet memes. However, this is not to assume that all memes of this kind must involve the internet; I will consider possible exceptions later on. From now on I will simply call internet memes ‘memes’.

Evnine makes a distinction between a conceptual and an ontological definition. If the question is ‘What is an X?’, the conceptual definition provides informative, non- question-begging necessary and sufficient conditions for a concept X, while the ontological definition describes the metaphysical nature of the things that fall under the concept X. I appreciate this distinction and will address them separately. Evnine also acknowledges that the word ‘meme’ – meaning an ‘internet meme’ – is used in two slightly different senses. One is a meme-trend, of which there are many different instances, such as the Distracted Boyfriend meme, which involves users labelling a stock photo of a man admiring a passing woman while his girlfriend looks at him, appalled. The other is a single instance of such a meme-trend, which one might send to a friend or share on Facebook, such as the specific Distracted Boyfriend meme in which the man is labelled ‘me’, the girlfriend ‘scientific evidence supporting the dangers of staring at the sun’ and the passer by ‘solar eclipse’.

Figure 3 : Distracted Boyfriend –solar eclipse / me / scientific evidence supporting the dangers of staring at the sun. Source: Know Your Meme

Where necessary, I will subscript the term ‘meme’ with CC or I, as Evnine has, to distinguish between common content (meme-trends) and instances.

Evnine’s Definitions

Evnine provides a very helpful description of how memes work, acknowledging the importance of the historical element (the context from which a meme has arisen), the affective element (their capacity to express emotions), implied narrative (the way that memes tell a story), and the self-aware nature of meme-making. Perhaps more than in any other art form, the practice and interactions surrounding a meme are key to what makes it a meme. Evnine calls this ‘memographic practice’, describing it as the ‘meta-level of activity’ in which memes are ‘discussed, commented on, up-voted, down-voted, criticized, collected, replied to in kind, and so on’. In short, memographic practice is the particular way in which memes are used, rapidly shared and interacted with. It is such an essential factor of memes, Evnine argues, that ‘one cannot tell that something is a memeI merely by looking at it’.

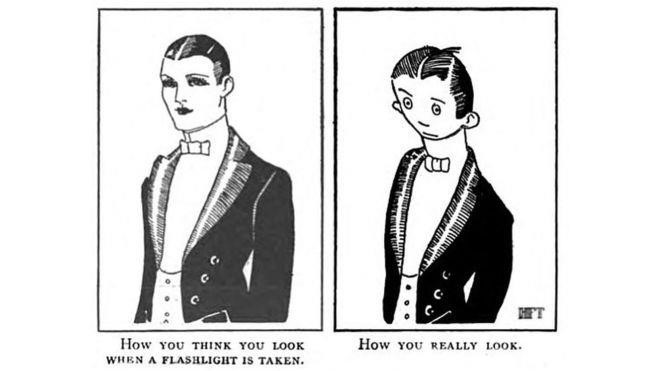

It could be argued that there are counterexamples to this view which show that it is the format and style of a piece of media that makes it a meme, not the practice surrounding it, i.e. M is a memeI if it has certain content conventional to meme- making such as reaction-based imagery, implied narrative, etc. A 1921 cartoon from the satirical magazine The Judge was brought to attention online in 2018 and referred to by some as the first recorded memesI [6].

Figure 4: A 1921 cartoon from The Judge. Source: BBC

It is understandable why people instinctively viewed this artwork as a memeI; it is a format-dependent narrative joke, with a relatable self-deprecating tone, and it follows almost exactly the template of the Expectation vs. Reality meme format [7]. However, I believe that there are two errors involved in the view that this is a memeI. The first is the failure to distinguish the cartoon as it was originally published in a print magazine from the cartoon as it is shared online today. The former is an original artwork created by an illustrator with the intention that it would be delivered to an audience who would look at it, laugh, and eventually throw the magazine away. The latter is a digital rendering of the artwork which is shared on several media platforms to be discussed, commented on, criticised, collected, etc. It can be (and indeed has been) appropriated by users to make other memesI, giving rise to a memeCC. Therefore, it seems likely that when people refer to this artwork as a memeI, they are really thinking of its digital reincarnation, which, in my view, is a memeI, while the original artwork is not.

The second error is the implication that, whether the artwork is engaged with memographic practice, it is nonetheless a meme because of its format and style. To view a standard meme format as a sufficient condition for something to be a meme could take us adrift from how the concept is used; it would require us to consider as memes things that look like memes by accident. If molecules in space somehow arranged themselves in a way that, coincidentally, looked like a meme, it would be regarded by almost no-one as actually being a meme, partially because it would not have the intention of a meme-maker behind it. Therefore, stylistically resembling a meme is not a sufficient condition. Nor, as I will argue below, is it necessary.

The memes that Evnine uses for examples are relatively traditional in style1 , but the importance of memographic practice in the essence of memes has become increasingly apparent in recent years as the norms of format and style have been flouted. For example, there is the meme genre of ‘cursed images’, which are found photographs, often poor quality and flash-lit with subtly disturbing or mysterious content, taken out of their original context and collected in a memographic one. The subject matter tends to be one step away from the banal, such as a child surrounded by people in creepily inaccurate cartoon character costumes at a birthday party, or a photocopier covered in spaghetti, and they make the nauseated viewer wonder how the depicted situation came about. These narrow requirements make the collection of cursed images a respected discipline on Facebook pages and subreddits. But in terms of format, they are simply photos, unmanipulated; they have only become memes by being shared in this way. There are many similar examples of found memes which, like other found artworks, are memes only by virtue of being taken up into memographic practice.

Figure 5 : An image featured on the Facebook group ‘Toilets With Threatening Auras’

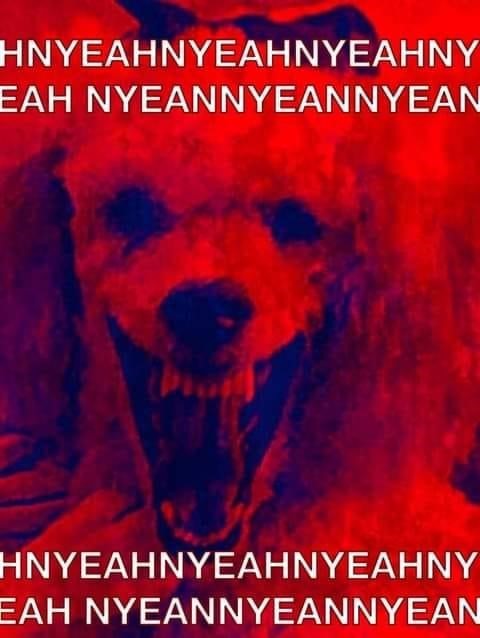

In fact, many avant-garde memes pages today play on the fact that the memesI are so dependent on their context2. The meme page or area of meme-subculture can serve as a gallery space in which pieces of media are granted memesI status, and in many cases the humour and affect are far better understood through the collection as a whole than through the individual memesI. For example, the Facebook pages ‘ 神は部屋を出ました’ (‘God Has Left the Room’) and ‘Pains of Hell Wellness Clinic’3 share surreal memesI that fit into an implied overarching narrative that we – the viewers and the page creators – are living in a quasi-supernatural schizophrenic hellscape. Some of these memesI, which would be fairly nonsensical to the uninformed viewer, contain highly distorted or pixelated images of demonic-looking faces with contrastingly banal or colloquial captions. Others are uncaptioned images, often with a ‘cursed’ aesthetic or relating to hell.

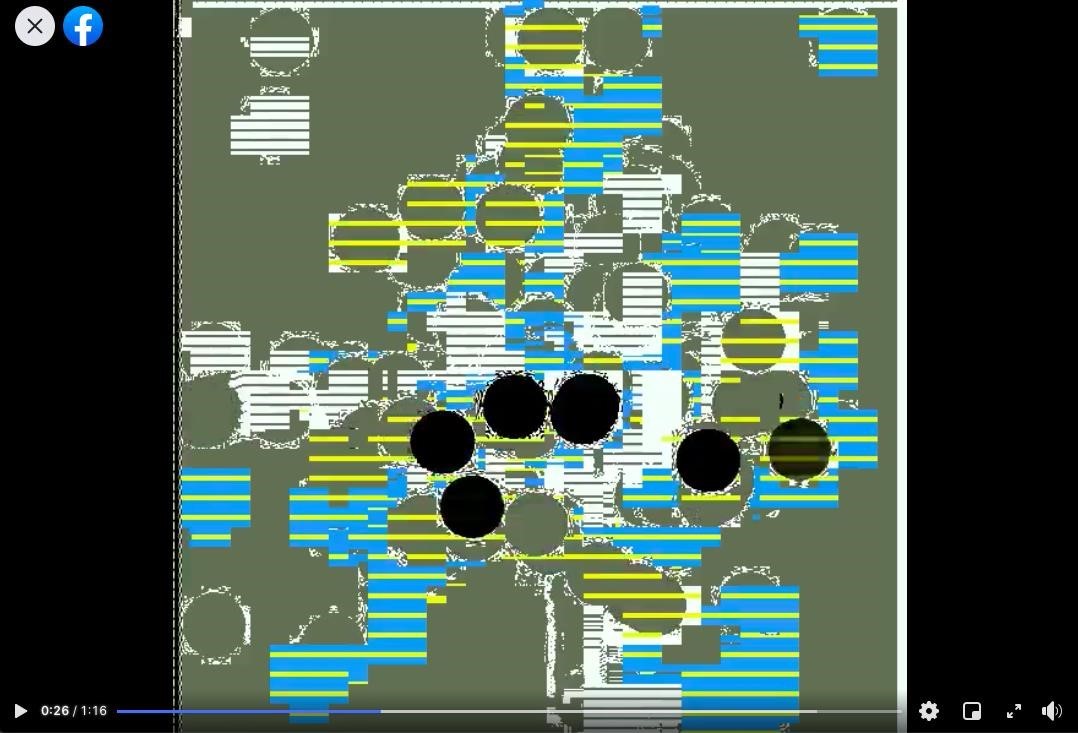

Figure 6: An image on ‘Pains of Hell Wellness Clinic’, parodying the traditional top-text- bottom-text image macro format in a way that is intentionally chaotic, unsettling and incoherent

Figure 7: A screenshot of a video posted onto the Facebook page ‘God has left the room’

But other memesI on these pages challenge the norms further, such as a video on ‘God Has Left the Room’ depicting black dots moving haphazardly and trailing compression artefacts on a jarring glitch-like background (Figure 6), with a piercing high-pitched buzzing throughout. The content is devoid of concrete meaning, but the video’s tone is somehow consistent with that of the other memesI on the page; perhaps there is an implicit invitation for the users to pretend, as characters in this dystopian digital plane, that we are witnessing ordinary media content or a representation of our daily reality. The video received many ironic heart-reacts and laughter-reacts as well as ironic comments such as ‘Haha funny video’. MemesI such as this are a challenge to the viewer, daring one to accept them as memesI, much like early 20th-century Dadaist art challenged viewers to accept it as art.4 Such cases demonstrate that no particular form or content is necessary for a meme, but memographic practice – the maker’s memographic intention – is necessary; it is as essential to a meme as a listener’s auditory experience is to a musical work.

Having argued for the importance of memographic practice in the essence of memes, Evnine provides some ontological and conceptual definitions. Since they are different types of definitions, they are not mutually exclusive, but rather describe memes from different angles.

| MemeCC-Con […]: M is a meme if and only if M is made, as part of memographic practice, out of norms for producing things as part of that memographic practice. |

| MemeI-Con: M is a memeI if and only if M is an instance of a memeCC. |

| MemeCC-Ont […]: A meme is an abstract artefact made out of norms. |

On the matter of an ontological definition of a memeI, Evnine states that ‘there is simply no general account’, since memesI can take the form of images, actions, words, and so on.

Evnine’s ontological account of memesCC is fairly uncontroversial (unless one has a metaphysical issue with abstract objects in general). The majority of this paper will be focussed on the conceptual definitions.

It is implicit in Evnine’s definitions, and explicit in his paper as a whole, that his definition of memes is a relatively broad one. He has provided apt restrictions on the concept, requiring that a meme arise from memographic practice. He acknowledges that a memeCC cannot be reduced to any specific image or instance, but to an abstract object made up of a set of norms to which its instances adhere. However, Evnine acknowledges as memes cases that many people who are deeply engaged in memographic practice would dispute. For example, Planking, the trend in which a person extends herself in a rigid horizontal position in an unexpected place (e.g. across a public bannister) and uploads a photo of it online, is a memeCC for Evnine. So is #scalebackabook, a hashtag associated with Twitter users writing imaginary book titles that are considered milder versions of real ones (e.g. Pride and Slight Bias instead of Pride and Prejudice). These examples would normally, from all my experience of discussing social media with those who are most engaged with it and gathering opinions online5, be considered mere online trends, not memes. Furthermore, Evnine theorises a scenario in which people develop a self-aware practice of handshaking in which each handshake is a riff on, development of or response to a previous one, and imagines that these handshakes could be considered memes. This raises the question of whether something must be online in order to be a meme, and also whether a joke or trend being online is sufficient for its status as a meme. A trend such as #scalebackabook resembles memes in that it is spread online, but one could imagine a similar trend occurring in a conversation between friends, in which case there is reason to doubt that even Evnine would consider it a meme. By allowing any comedic online trend to be called a memeCC, and simultaneously discounting digitality as a necessary condition, Evnine risks allowing all running jokes or trends – even ones shared between friends in oral conversation – to be memes, which could lead the definition to fall apart into a drastically broader concept like a Dawkinsian meme. I will explore in the section titled ‘Other Central Properties of Memes’ the issue of digitality and further hypothetical scenarios that highlight issues in defining a meme, but for now I will lay out some immediate problems that arise from Evnine’s definitions.

Problems with Evnine’s Account

Evnine neglects to provide an ontological definition of a memeI, leaving ambiguity as to whether a memeI is necessarily an abstract object.

Evnine’s account leaves ambiguity as to what is sufficient for something to be part of memographic practice. Although his initial description appears to only apply to social media, the handshaking example suggests that memographic practice could exist outside of the internet.

Evnine does not directly address some significant, perhaps necessary, factors of memes: digitality, comedy, anonymity, ephemerality and appropriation.

I will begin addressing the more straightforward aspects of these problems, the first being the ontological status of a memeI. Evnine conceptually describes a memeCC as a set of norms for producing ‘things’. He expands on this, stating that these ‘things’ can be ‘images, videos, songs, imaginary book titles, or anything else’. However, there is reason to assume that this ‘anything’ does not extend indefinitely. A concrete object is never itself meme; to pick up a water bottle and say to someone, ‘What do you think of this meme?’ would leave them mystified as to how it, a concrete object, could be a meme. What unifies Evnine’s examples is that they are abstract (I am counting images, videos etc. as abstract since, like novels, they have multiple concrete instances and are not reducible to their instances). There are cases that could be considered counterexamples to the abstract status of memesI, such as memesI which have been printed out or made into something tangible in some other way. However, even if one accepts that the memesI remains a memeI when it is printed out, there is no substantial metaphysical difference between this case and the case of a meme being physically manifested on a smartphone screen. The abstract object is represented by the concrete one, but is abstract nonetheless, just like a pound in money being represented in the form of a coin. It seems that Evnine and all other theorists are working under the sound implicit assumption, then, that memesI are abstract objects. This resolves problem 1.

Another straightforward issue is the factor of comedy. Whether or not a meme makes one laugh, it is never without comedic intent. As Evnine acknowledges, there are many affective elements to a meme; the formal devices can convey a tonal complexity worthy of extensive analysis. Memes can be political, surreal or sad, but the central expressive aim is always humour. That comedy is essential to memes does not appear to be a disputed claim, but simply a fact that Evnine neglected to explicitly address. It is worth noting, though, that media content without comedic intent is very often appropriated and made into memes, but in these cases the media content itself is not the meme, merely a source. This resolves one element of problem 3.

There is ambiguity in Evnine’s definition as to how public ‘things’ have to be in order to be memes. This ambiguity lies in what is sufficient for something to be ‘part of that memographic practice’. It seems clear that an oral inside joke within a friendship group is not a memeCC in the sense that I am exploring – if not because it is not online, then because it cannot spread in the wider public sphere; it is fated to remain local and personal. However, it is common for memographic practice to occur in online group chats or private Facebook groups; people make memesI-like images that are only understandable to a particular audience, and other members of the group interact with them memographically. Although these things are no more public than oral in-jokes, they are normally referred to as memes and intuitively seem more meme-like. So, what differentiates group-chat memes from oral in-jokes?

It is implicit in Evnine’s definition that a memeI must arise from memographic practice, but what must be done with it after its creation is less clear. It seems that the important factor is not whether something actually spreads into wider public memographic practice, but whether it can directly be spread in this way. Suppose I have created a memeI but have not got around to sharing it. To say that it would only be a memeI from the moment it is shared seems too strict and counterintuitive. In the case of group-chat memes, or memes that have not yet been shared, part of what makes them memes is that they are publicly shareable, one click away from being shown to the world.

Of course, there is room for disagreement over how (potentially) public memes must be. Publicness is a relative concept, and potential is a vague one. The intention behind a meme may play a part in the factor of potential since something not intended to be seen by anyone would likely not be considered ‘publicly shareable’ enough to be a meme. I will not attempt to draw a hard line for the degree of public shareability something must have to be a meme, but I will conclude that public shareability as part of memographic practice is a necessary condition. I say ‘as part of memographic practice’ because a memeI must be shareable in such a way that memographic practice around it can continue. For example, a joke that has arisen from memographic practice could be made in a film, but it would not be a memeI because its audience would not be able to engage with it memographically (up-vote it, comment on it, etc.).

I believe that there are factors other than public shareability that make the case of the group chat more meme-like than that of oral jokes, but I will explore these in the next section.

For now, we can address problems 1 and 2 with the term ‘media content’, meaning publicly shareable abstract objects. With the solutions that I have provided so far, our revised conceptual definitions of a meme can look like this:

| memeCC-Con (first pass): M is a meme if and only if M is made, as part of memographic practice, out of norms for producing comedic media content as part of that memographic practice. |

| memeI-Con (first pass): M is a memeI if and only if M is an instance of a memeCC and is publicly shareable as part of memographic practice. |

As a concise account of memes, this seems more accurate than Evnine’s. However, there remain issues in this definition that are exemplified by borderline cases. The issue of public shareability is interwoven with other issues that I believe to be central properties of memes. In following section, I will discuss the properties of digitality, anonymity, ephemerality, appropriation, and use of images and/or text.

Other Central Properties of Memes

Some of the most challenging borderline cases are of non-digital ‘memes’. When a memeI that originated online is printed onto paper at home, it becomes intuitively less meme-like. This is partly because it is made static and local; it is bound to a physical space and cannot multiply across the world or be copied, appropriated and edited in the way that digital memes are. The memesCC from which it came could continue to evolve and be publicly engaged with, but the printed memesI would remain disconnected from memographic practice. However, the situation might be different if printed images were shared in a public context. Suppose that pupils of a large school pasted meme-like images on the walls. These could be commented on in graffiti and conversations, and their style could evolve via photocopying to become continuous, self-referential streaks of narrative humour. This could be meme-like enough to be considered by many as a case of memes. But how far can we extend the possibility of non-digital memes without over generating?

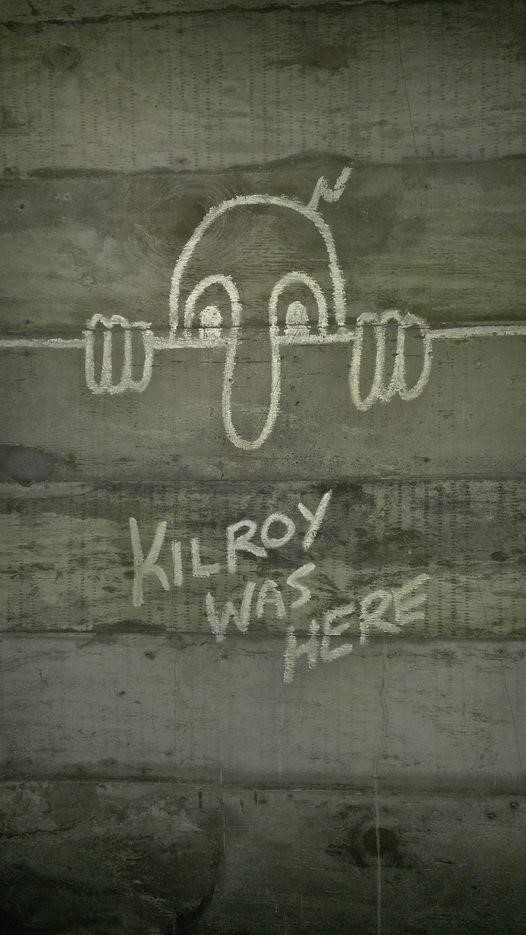

During the Second World War, ‘Kilroy was here’ – an American symbol depicting a cartoon figure peeking over a wall – began to spread in the form of graffiti. Members of the public would write ‘Kilroy was here’ and often accompany it with the illustration. According to author Charles Panati, ‘The outrageousness of the graffiti was not so much what it said, but where it turned up.’[11] A similar-looking graffiti cartoon, referred to as ‘Mr Chad’, appeared in the UK at a similar time, captioned with ‘Wot, no sugar?’ or a similar ‘Wot, no – ?’ phrase bemoaning rationing[12]. The public ownership and re-use of these images, with the context of each instance feeding into its humour, and, in the case of Mr Chad, the variation on the phrase used, render this case quite meme-like. But, of course, it does not have the same engagement with memographic practice as online memes do. It also differs from online memes in that it is a case of hand-drawn images that exist in specific locations. It seems that, even if we accept that digitality is not a necessary condition for something to be a meme, it is required in practice to meet some other conditions that could be seen as necessary, which I will discuss below.

Figure 8 : An instance of ‘Kilroy Was Here’ at The National WWII Museum in New Orleans. Photo by Laura Gibbons Barnett. Source: Facebook

Figure 8 : An instance of ‘Kilroy Was Here’ at The National WWII Museum in New Orleans. Photo by Laura Gibbons Barnett. Source: Facebook

It seems generally agreed among theorists6 that collectivism of some sort is a necessary part of meme-making. Giselinde Kuipers argues that ‘Like the jokes and stories of oral culture, Internet jokes have no authors (unless everyone is an author)’ [13]. Memes, unlike most art forms, have a detachment from personal gain or credit. For a meme to flourish, it is ideally not bound to any name; anyone should be able to take a memeI and, with simple editing, turn it into another. For this reason, watermarked memesI are criticised in meme-sharing communities; the sense of public ownership, and thereby quality, is compromised by the watermark. The factor of anonymity is one of the things that make #scalebackabook a borderline case – or, in my opinion, not a case at all. When an individual writes her own words on Twitter,

Facebook or similar, the words are attached to her identity, and every time her words are shared her account will get credit for it (e.g., in the form of likes or retweets). I believe that this is the reason that, when Tweets and Tumblr posts are shared as memesI, they are done so as screenshots as often as retweets or reblogs. The contents are then detached from their author, no longer owned by an individual, and can be manipulated and spread as much as internet users would like. Then, it is part of the collective.

What I am calling anonymity is a kind of collectivism that goes beyond that of an oral tradition or graffiti trend. When content is appropriated for an online meme, it is not re-drawn by the user’s hand or re-spoken in her voice; it is directly replicated with no imprint of the user’s input. This total detachment from any author plays a crucial part in a meme’s tone, and it may be impossible to create the same tone in a memeI that is recreated, with the intention of direct replication, in a way that involves accidental human idiosyncrasies, such as by re-drawing or re-recording. So, although in a case such as Mr Chad the creator of each instance is unknown, it does not meet the anonymity condition in the same way that online memes do.

The anonymity condition is closely linked with another crucial factor which I will call ephemerality. There appears to be an implicit ideological tone that feeds into the format of memes. Memes are possibly the only art form that serves virtually no material benefit to its creators. They have, entirely self-consciously, a ‘low-art’ status. Memes are not made to be officially collected, go down in history, or communicate universally. Perhaps their (usually) digital nature is a matter of not being given the respectable status of physical existence, because they are, essentially, silly – too silly to be anything other than ephemeral. Each memesI is waiting to be altered or discarded, dependent on the time in which it arose. It is part of the joy of memes that if a future archaeologist were to uncover a memeI of today, she could be baffled. Therefore, I believe that if a meme were chiselled onto the side of a skyscraper, as a commission from the Tate Modern, it would cease to be a meme because its ephemerality would be taken away.

Figure 9 : A Tumblr user’s appreciation of how incomprehensible the above meme would be to an uninformed viewer. The meme follows a format based on a cartoon character gesturing to a butterfly and asking, ‘Is this a pigeon?’. The format is used to represent someone mistaking something for something else. In this case, the figure represents a cat gesturing to ‘my lap’. The photo of the man’s face is, in memes, associated with the phrase ‘It’s free real estate’. So, the situation depicted in this meme is a cat regarding its owner’s lap and considering it ‘free real estate’, i.e. its own property in which to sit. Source: Dopl3r

Figure 9 : A Tumblr user’s appreciation of how incomprehensible the above meme would be to an uninformed viewer. The meme follows a format based on a cartoon character gesturing to a butterfly and asking, ‘Is this a pigeon?’. The format is used to represent someone mistaking something for something else. In this case, the figure represents a cat gesturing to ‘my lap’. The photo of the man’s face is, in memes, associated with the phrase ‘It’s free real estate’. So, the situation depicted in this meme is a cat regarding its owner’s lap and considering it ‘free real estate’, i.e. its own property in which to sit. Source: Dopl3r

For Ryan Milner, appropriation is one of the fundamental logics central to memes [14]. But Milner implicitly allows to be memes content such as original YouTube or TikTok footage of people, and photos that follow a trend (e.g. Planking), which, according to most informal contributors in today’s memetic discourse, are not memes (see footnote 5). At least part of the reason for this general opinion, it seems, is because each instance is made up of original content which, strictly, meets neither the anonymity nor the appropriation condition. Since the start of their existence, memes in the narrower sense have almost always been made up of content taken directly from other uncredited sources. This, like the anonymity factor, contributes to their implicit ideological tone. There are, of course, exceptions. The ‘God Has Left the Room’ video memesI appears to be made up of original graphics. Many meme formats involve repeated use of particular drawings, which in many cases were likely created for the purpose of the meme, and occasionally other media such as photos form the common content of a memeCC, having been created for this purpose.

However, these cases seem to follow a rule: the content created for the purpose of a meme must not resemble ‘high art’. Even the ‘God Has Left the Room’ video is pushing this boundary; most images created for contemporary memes are low-skill, low-fi digital drawings with an anti-aesthetic or vulgar tone (such as Wojak [15] and its variants). Even so, the first online appearances of these meme-drawings could certainly count as borderline cases due to their original content.

Figure 10 : Wojak, a character featuring in contemporary memes. Many characters have been created with this as an illustration template in the ‘Wojak comics’ genre of memes.

Figure 10 : Wojak, a character featuring in contemporary memes. Many characters have been created with this as an illustration template in the ‘Wojak comics’ genre of memes.

There do not appear to be any online memes that do not use images and/or text. But seeing as memes span the media of text, photos, drawings and videos, no particular media format seems tied to the essence of memes. The use of images and/or text appears to be a practical limitation; memes would simply not be able to spread or be consumed and replicated as easily and anonymously if they existed in non-visual forms. There is an auditory trend in surreal, kitsch video memes of extreme bass boosting7. In these videos, which often involve intentionally tasteless and incoherent graphics, the bass boost provides a level of distortion that makes the sound quality far enough from reality and everyday voice communication for the anonymity factor to be maintained. In theory, memes in this style could exist only in sound format. However, there would probably be less room for stylistic variation and evolution in purely auditory memes.

This brings us back to the issue of non-digital memes. Clearly the case of Mr Chad does not meet the anonymity, ephemerality and appropriation conditions to the same extent that online memes do. Its instances are limited by their physical nature and the fact that they are copied by hand. Furthermore, there is barely any memographic practice surrounding it. Evnine’s handshaking example runs into similar issues. Firstly, each instance of the handshaking ‘meme’ would be executed through physical touch and movement, which limits the appropriation and anonymity factors. Secondly, handshakes are private and local; these ‘memes’ would have to exist in a society in which it was customary to shake hands with people many, many times a day to get close to the level of publicness required for something to be a meme. Thirdly, the extent to which one can communicate and replicate complex ideas in a handshake is, practically speaking, extremely limited. Finally, if we accept that handshakes can be memes, there is nothing to prevent us from accepting all running jokes as memes, or even all conversational threads, and this would be straying too far from how the term is used. Digitality, although it may not be strictly necessary conceptually, is almost always practically necessary for something to meet the anonymity, ephemerality and appropriation conditions of a meme.

Defining a meme

I have outlined what I view to be some central properties of memes. I will not, however, make the strict claim that they are necessary conditions. There are exceptions to the appropriation condition, as there are some memes that use original images or audio. There are at least quasi-exceptions to the anonymity condition, since some memes circulate in the form of text-based Tweets, for example. And I will not rule out the idea of exceptions to the ephemerality condition. There is also ambiguity as to the degree to which a case must meet these conditions since they are relative concepts. However, in cases where something that is intuitively a meme fails to meet one of these conditions, it is crucial that it sufficiently resemble a meme in other ways. Generally, a meme made from original (non-appropriated) images, for example, must meet the conditions of digitality, anonymity, ephemerality and use of images and/or text.

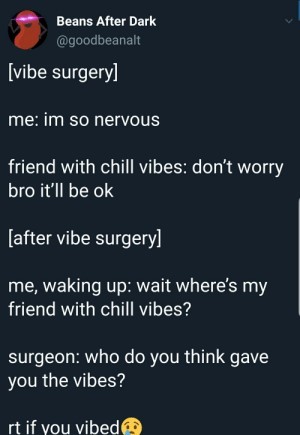

Figure 11: @goodbeanalt’s Tweet about ‘vibe surgery’

Figure 11: @goodbeanalt’s Tweet about ‘vibe surgery’

An example such as the above image will be commonly accepted as a memeI. The anonymity factor is slightly compromised by its being a text-based Tweet – but this is true of many memes. What, then, makes this so much more meme-like than an instance of the #scalebackabook trend? The ‘author’ of the memesI is not speaking as themselves; they are speaking ironically within a narrative which takes the script-like format of many text-based memes. This narrative is a direct parody of a style of oft- copy-pasted blocks of text that spread around the internet in the 2000s, one of which described a girl going in for heart surgery, waking up afterwards and realising that her boyfriend has donated his heart to her. The original versions normally ended with a message along the lines of ‘share if you cried’, which has been parodied as ‘[retweet] if you vibed’. This Tweet invites users to play along by pretending to be moved by the surreal version of the narrative in which people can donate ‘vibes’ in that way that people donate organs. So, in this case, it is a meme because it has clearly arisen from memographic practice – adopting the script-like meme format – and used an appropriated text template. An instance of #scalebackabook, however, does not use a format or style, or a variation on a format or style, that is used in memes, and only appropriates to the extent that it parodies a book title. Perhaps a similar trend could count as a memeCC if there were a character created by users, represented using appropriated images and low-skill, low-fi digital drawings, who was known for their scaled-back, feeble nature, and who was depicted holding a book whose cover were a digitally manipulated version of a real book cover, displaying the ‘scaled-back’ title. This would involve a lot more appropriation, anonymity (since the words used would be more separate from their writer by virtue of the image format) and, crucially, with its implied narrative, stylistic resemblance to other memes. Therefore, although style and content alone cannot make something a meme (as I have argued in an earlier section), it seems necessary to consider stylistic resemblance to other memes as one of the central properties, since it is a factor that could make an otherwise borderline case count as a meme.

So, we have the necessary conditions of memes: arising from memographic practice, public shareability as part of memographic practice, and comedic intent. We also have some central properties of memes: digitality, anonymity, appropriation, ephemerality, use of images and/or text, and stylistic resemblance to other memes. From this, we can put together another Evnine-style conceptual definition.

memeCC-Con (second pass): M is a meme if and only if M is made, as part of memographic practice, out of norms for producing, as part of that memographic practice, comedic media content which has at least five of the following six properties: digitality, anonymity, appropriation, ephemerality, use of images and/or text, and stylistic resemblance to other memes.

memeI-Con (second pass): M is a memeI if and only if M is an instance of a memeCC that is publicly shareable as part of memographic practice and has at least five of the following six properties: digitality, anonymity, appropriation, ephemerality, use of images and/or text, and stylistic resemblance to other memes.

If I were determined to conclude with a concise, formal definition outlining the necessary and sufficient conditions for being a meme, this is what I would provide. But, intuitively, as a descriptive definition, this seems too strict. An expert on memes would surely be able to present me with an undeniable case of a meme that meets only four of the above conditions, or a case that meets five of the conditions and should not count as a meme.

Morris Weitz argued that to make a closed definition of art, or its sub-concepts such as opera or portraiture, ‘is ludicrous since it forecloses on the very conditions of creativity in the arts’ [17]. Memes, whether or not they are respected, are a kind of art form, and it seems more fitting than any other approach to treat the concept of memes as an open one. In the philosophy of art, a ‘cluster’ definition is one that employs Wittgenstein’s theory of ‘family resemblance’, a way of describing open concepts not with jointly necessary and sufficient conditions, but with a ‘network of similarities’ [18]. The things that fall under such a concept have many traits in common with each other, but there is no trait that all of them have. A may have things in common with B, and B things in common with C, but there be no one thing that is shared by A, B and C – much like resemblance within a family, whose members share a resemblance in their features, but there is no one feature that all members have (they do not all have the same nose, for example). Proponents of the ‘cluster’ view suggest that art and art forms should be defined in this way, and typically provide a list of traits that count towards something is being a work of art, none of which is a necessary condition. This type of account could be applied to memes, with the properties in the cluster being as follows: comedic intent, arising from memographic practice, public shareability as part of memographic practice, anonymity, appropriation, ephemerality, digitality, use of images and/or text, and stylistic resemblance to other memes.

However, to do this would be to discount the conditions of comedic intent, arising from memographic practice, and public shareability as part of memographic practice, as being necessary. This would leave us with a definition that massively over generates; any entity that is ephemeral, or any entity that is anonymous, could count as a meme. Therefore, the necessary conditions must be kept. My definition, then, will neither be the traditional list of jointly necessary and sufficient conditions, nor a completely loose ‘cluster’ concept; it will take elements of both.

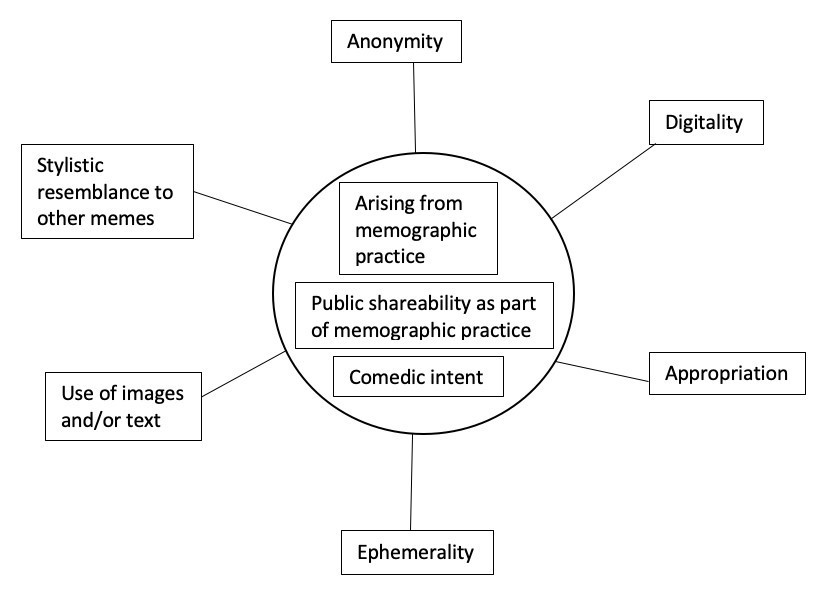

Figure 12 : A diagram illustrating the concept of a meme

As I have illustrated above, I will regard the necessary conditions as the nucleus of the concept of a meme, and the other central properties as closely surrounding it. Although I maintain as a general observation that memes meet at least five of the six central conditions, I will, in the spirit of Weitz and of creativity, refrain from stating this as a rule.

Conclusion

I have responded to Evnine’s ontological definitions, concluding that both memesCC and memesI are abstract objects. I have critiqued his conceptual definitions of memes, arguing that they over generate. I have provided a narrower in-depth account of the concept of memes, listing necessary conditions and ‘central’ conditions for something to be a meme, acknowledging ambiguity and leaving room for the creative flouting of norms. Therefore, I conclude with a description of memes consisting of three necessary conditions and six central properties. If my description, illustrated by the above diagram, is X, then M is a memeI if it is X, and M is a memeCC if it is made out of norms for producing X.

This article was reproduced with the kind permission of University of Bristol.

Bibliography

[1] Evnine, Simon J. “The Anonymity of a Murmur: Internet (and Other) Memes.” The British Journal of Aesthetics, 58(3), 2018, 303-318.

[2] Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 1989 189-201.

[3] Shifman, Limor. Memes In Digital Culture. Boca Raton, CRC Press, 2015.

[4] Milner, Ryan. The World Made Meme: Public Conversations And Participatory Media. MIT Press, 2016.

[5] Know Your Meme. 2020. Money Printer Go Brrr [online] Available at: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/money-printer-go-brrr [Accessed 4 January 2021].

[6] Gerken, T., 2018. Is This 1921 Cartoon The First Ever Meme?. [online] BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-43783521 [Accessed 4 January 2021].

[7] Know Your Meme. 2015. Expectation vs. Reality [online] Available at: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/expectation-vs-reality [Accessed 4 January 2021].

[8] Facebook. 2021. Memes Without Bottom Text. https://www.facebook.com/memeswithoutbottomtext [Accessed 7 January 2021].

[9] The Philosopher’s Meme, 2016. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCT1K7lBP4fkxdlHaJAqjpaw [Accessed 7 January 2021].

[10] Unknown user, 2017. [META] I created an analysis of postmodernism in memes [online]. Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/surrealmemes/comments/61szun/meta_i_created_an_ analysis_of_postmodernism_in/ [Accessed 4 January 2021].

[11] The Straight Dope. 2000. What’s The Origin Of “Kilroy Was Here”?. [online] Available at: https://www.straightdope.com/21342952/what-s-the-origin-of-kilroy- was-here [Accessed 4 January 2021].

[12]^

[13] Kuipers, Giselinde. “Media culture and Internet disaster jokes.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, 5(4), 2002, 450-470.

[14] Milner, Ryan, “Logics: The Fundamentals of Memetic Participation.” In The World Made Meme

[15] Know Your Meme. 2015. Wojak. [online] Available at: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/wojak [Accessed 4 January 2021].

[16] Socialism Done Left, 2020. I don’t deserve you, you should be with a real girl…. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SBI6uwUiGHE

[17] Weitz, Morris. “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 15(1), 1956, 27-35.

[18] Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations (1953). Translated by E. Anscombe. Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1997.

Evnine’s primary examples are Socially Awkward Penguin and Batman Slapping Robin, which both became popular in the 2000s. While these examples are helpful in laying down the basics, I find it necessary to consider more recent examples when exploring the concept of a meme, just as it is necessary to consider postmodern art when exploring the concept of art. ↩

One of the defining features of what I am calling ‘avant-garde’ memes is that they self-consciously deconstruct and upturn the norms of meme-making. Many avant-garde memes do not contain a joke per se, but exist for the sake of direct anti-aesthetic appreciation; such memes often have a comedic effect that may be impossible to explain to an unappreciative viewer. Example: ‘Memes Without Bottom Text’ (Facebook page and meme genre) [8] ↩

Warning: both of these pages contain violent or disturbing images and insensitive humour. ↩

See ‘Memes: A Microcosm of Art History’, a lecture series by YouTube channel ‘The Philosopher’s Meme’, for an expansion on this comparison[9]. For something more concise and digestible, see (in Bibliography) this slideshow shared via a Reddit account. [10] ↩

Most academic theorists on memes have provided an account of memes that is at least as broad as Evnine’s. But in providing a descriptive account, rather than a prescriptive definition, I consider it crucial to consider, above anything, the opinions of those most involved in meme-making and memographic practice. On analytical meme discussion pages such as the Facebook group /tpmg/ - TPM Meme Research and Development, the artifacts discussed fall into a narrow category that would not include the likes of Planking or #scalebackabook. Colloquially, too, the word is applied in the narrower sense, although it appears to be used more loosely by the general public than by those deeply involved in memographic practice and analysis. On a survey conducted via the anonymous university confession platform Bristruths, 78% of the 382 who responded believed that Planking is not a meme but merely a trend, since a meme is something more specific. ↩

See Shifman and Milner ↩

E.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SBI6uwUiGHE [16] ↩