Memes and Humor: Reply to Claudia Vulliamy's "What is a Meme?"

Simon J. EvnineIn her very interesting essay for this website, “What is a Meme?”, Claudia Vulliamy critiques a definition of the concept meme that I gave in my paper “The Anonymity of a Murmur: Internet (and Other) Memes” and replaces it with what she argues is an improvement. I maintained that for something to be a meme it is necessary and sufficient that it be “made, as part of memographic practice, out of norms for producing things as part of that memographic practice.” This is intended as a definition of a type of meme, such as Batman Slapping Robin – what Vulliamy calls a meme trend – and not of the individual things that manifest a trend or instantiate a type. Defining a meme as being constituted by norms gets at the idea that a meme is basically just some instructions that tell you to use a certain image, put a certain kind of text on it in a certain position, and so on. By “memographic practice” I mean a particular, historical phenomenon that began around the end of the 20th century on internet message boards and gradually migrated to the internet at large and even, arguably, to the non-digital world. The reference to memographic practice distinguishes memes from, say, sonnets. The sonnet is also to be identified with some instructions, instructions that prescribe number of lines, rhyme scheme, etc. But it is not a meme, in the relevant sense, since it operates in a totally different socio-cultural-historical context. Vulliamy agrees with me that being (or being made out of) a norm or norms for producing things as part of memographic practice is a necessary condition on being a meme but she disputes its sufficiency. That is, she thinks my definition over-generates, counting as memes things that are not. She adds two further necessary condition and six further conditions whose status will require investigation. The two further necessary conditions are that a meme must be publicly sharable as part of memographic practice and that it must be made with comedic intent. The six further conditions are ephemerality, anonymity, digitality, appropriation, use of images and text, and stylistic resemblance to other memes. About these six conditions, Vulliamy writes: “Although I maintain as a general observation that memes meet at least five of the six central conditions, I will… refrain from stating this as a rule.” In an earlier superseded definition, however, Vulliamy requires that for something to be a meme it must meet at least five of the six further conditions. It is unclear why the number five is chosen other than that it is the closest thing to holding that all six of the further conditions are necessary while still falling short of that. Nor is it clear why Vulliamy retreats from the stronger view. In any case, as I say, she seems to take a more relaxed attitude later on.

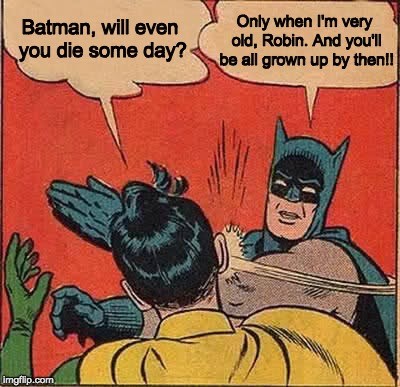

With the possible exception of comedic intent, I am in full agreement with Vulliamy on the centrality of all these conditions for understanding memes. (I have written about anonymity and appropriation in my forthcoming “Philosophy Through Memes” to be published in the Blackwell Companion to Public Philosophy.) So in matters of substance, I am deeply sympathetic to what Vulliamy writes. Again with the exception of comedic intent, I would say that the only space between Vulliamy’s position and mine is this. Do we implicitly agree over what memographic practice is but disagree over whether it’s enough to make something a meme? Or does Vulliamy have a narrower conception of memographic practice than I have? For example, I might think that making things that are digital, ephemeral, anonymous, etc., is internal to memographic practice and hence already covered in my original definition. But Vulliamy may think that memographic practice is to be understood in a more restricted way. Given that neither of us says a lot about what memographic practice is, it is hard to get at the source of our disagreement here. But I am inclined, now that I’m pushed, to say that all of Vulliamy’s extra explicit conditions other than comedic intent are characteristics of memographic practice. So I think I’m happy to accept what Vulliamy adds to my definition as a friendly amendment, making explicit something I should have been clearer about. It is only with regard to comedic intent that I balk. There are two scenarios to consider. In the first, a meme which perhaps – let us stipulate – does have among its associated norms the directive to make things intended to by funny is nonetheless used, intentionally, to make something not funny. This surely seems to be possible. Here is one I made just after the death of Adam West, the actor who played Batman in the 1960s TV series:

I hope this meme expresses some of the bafflement and the fear I felt when I had such a conversation with my mother as a child (and that all of us have gone through in some version or other). But it would seem wholly arbitrary to deny that this is a meme because it was not made with comedic intent. (I disregard here the fact that, as part of a book I am writing, the above is neither anonymous nor – I hope – ephemeral. These facts do indeed lead me to question its status as a meme and I have sometimes called it, along with others like it that I have made, an anti-meme.) Someone might counter that of course I must have had comedic intent, even if I simultaneously had some non-comedic intent as well. Placing Batman’s caring and parental words in an image in which he is slapping Robin is a predictable source of humor and as someone operating from within memographic practice, I had to be aware of that. Of course, the fact that the slap undercuts the words just makes explicit how inadequate the words are in ameliorating the slap in the face that is death and loss. But that doesn’t wholly negate the comedic aspect of it. One might generalize from this that, no matter how sad or dour some text is, the mere fact of placing it in an image, no matter how disturbing, from within memographic practice is bound to be humorous. Anyone who works as part of memographic practice must know this and intend the humor.

This seems a little too peremptory, though perhaps it’s not completely implausible. (“Dank” is the term that yokes humor together with the disturbing.) If it is correct, then the requirement of being made as part of memographic practice will include, along with ephemerality, anonymity and the others, something that I left implicit and that Vulliamy justifiably wants to make explicit. If it is not correct, then I must disagree with Vulliamy’s claim that comedic intent is necessary, at least with regards to the first scenario.

The second scenario to be considered is one in which the very meme trend itself is not associated with a requirement of comedic intent in its instances. It is true, at least as far as I am aware, that there are no genuinely tragic meme trends, relating to other meme trends as an elegy does to a limerick. But there is the phenomenon of wholesome memes. The relation between irony and wholesome memes is too complex to explore here but at least, prima facie, it seems that meme trends that do not demand comedic intent are possible. What response might Vulliamy make to this? One definition of “wholesome memes” found in Urban Dictionary is “memes made by normies for normies.” (Though I note that this definition has many more downvotes than upvotes!) Perhaps that is a reason to deny that the phenomenon of “wholesome memes” operates as part of memographic practice at all. True, there is the strong resemblance of wholesome memes to genuine memes in many respects, but so is there of genuine memes to limericks. (A question analogous to the one under discussion might be: can genuine limericks be made without comedic intent?) But we excluded those from counting as memes precisely on the grounds that the practice of producing limericks is not, as such, part of memographic practice. So perhaps too someone might hold that the practice around wholesome memes is not part of memographic practice. Indeed, perhaps “normies” are, by definition, excluded from participating in memographic practice. (Though this way lies a defense of the necessity of comedic intent that relies on the No True Scotsman fallacy.)

About the author: Simon Evnine is a professor of philosophy at the University of Miami. He is currently at work on a book, A Certain Gesture: Evnine’s Batman Meme Project and Its Parerga!, that includes over 100 Batman Slapping Robin memes (or anti-memes!) along with commentaries on each that deal with philosophy, psychoanalysis, language, and self-writing.