The Memetic Bottleneck

Seong-Young HerI. Simplifying Memes for Impact

One of my favourite techniques whenever I make a meme, take a screenshot, or edit anything else I make, is simplification. Simplification in these contexts usually means reducing redundancy and the number of steps required to get the intended meaning across. With memes, this usually means:

- making more references with fewer elements or components,

- getting to the punchline faster, and

- making that punchline more concentrated.

Here are some examples:

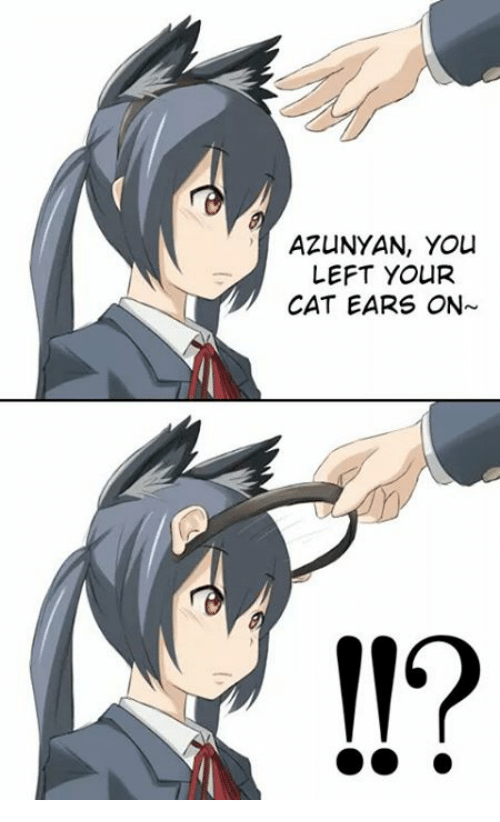

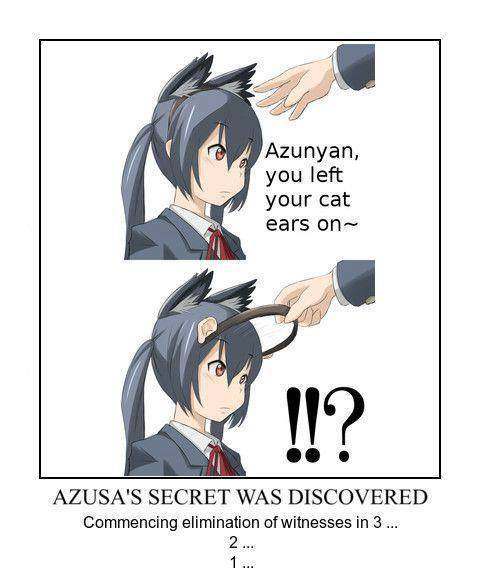

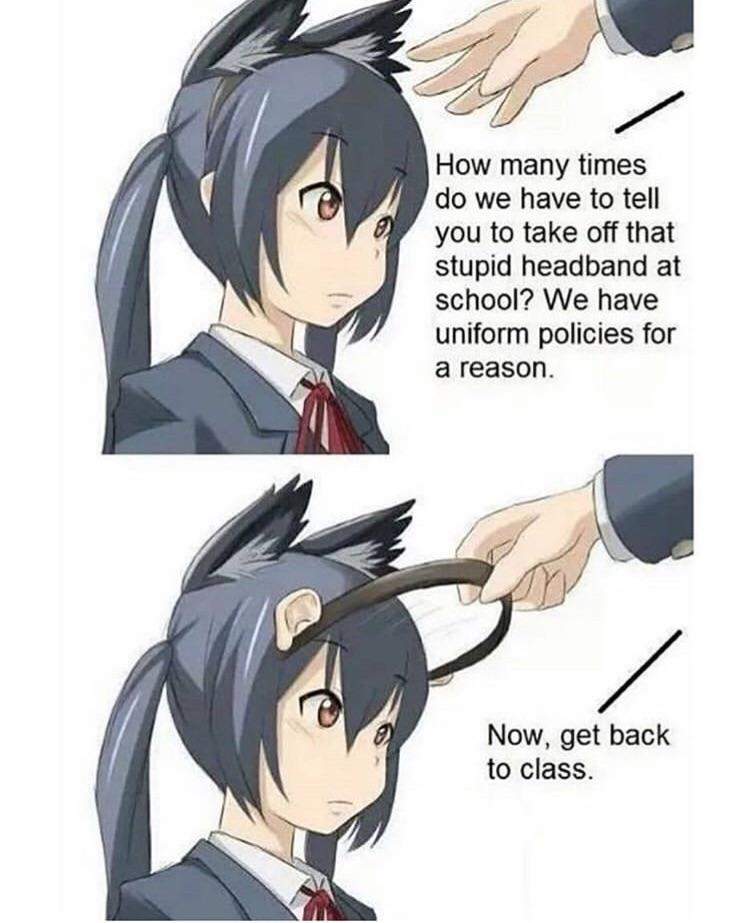

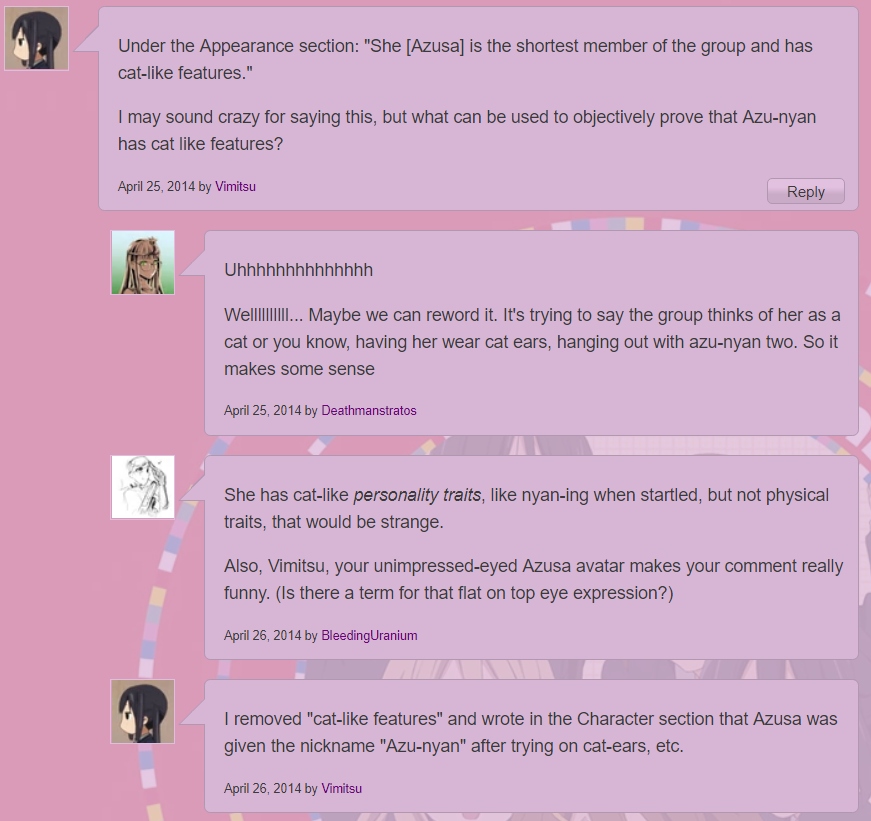

The other images begin with an elaboration, but the first image doesn’t. It doesn’t even have text except for “!!?”, which means the viewer doesn’t have to worry about reading the meme. The punctuation marks have the added benefit of being international. I strongly prefer the first image over the rest. I already know the trope of catgirls and cat ear headbands, and so I can understand the subversion of that trope without elaboration. If someone didn’t know the trope, they would either take longer to infer the joke from context or simply not understand the image. They might misinterpret the message as suggesting that catgirls without human ears should wear prosthetics.

Any additional information, such as that the character is a human from a mid- to late-2000’s slice of life manga and anime and that there is an inside joke about her catlike personality, does make the joke funnier because it makes the punchline even more unexpected. But since the notion that humans do not have cat ears unless they are wearing them on a headband is a standard belief, the additional information does not influence the comprehension of the comic.

If the information is new to the viewer, introducing it as the set-up would slow the progression of the joke and make it less punchy. Specifying the mode of appreciation for the punchline has a similar effect by interfering with the viewer’s free appreciation of the joke – which may deviate from the intended meaning. Timing is crucial to punchiness.

II. Memeing and Time

Most of these images are unambiguous instances of a two-panel comic. Two or three of them are likely to be classified as memes rather than comics. I think that comics are the closest established medium to Internet memes, and examples of comic panels being used as memes fit comfortably with this hypothesis.

Comic artist Will Eisner defines comics as a subgroup of sequential art: images ordered in a particular way to convey a narrative. Images in a sequence express the flow of time because they necessarily facilitate the synchronous flow of time for the reader. Time flows while the reader moves from one panel to the next. While panels can’t straightforwardly be considered units of narratological time without problems, they are useful to think of as some segment of time.

For example, consider recursive comics which force some panels to function as both chronologically before and after another panel. A recursive narrative might even allow for a single-panel comic to function the same way, instructing the viewer to read the sole panel multiple times. Comic panels are much more reliably understood as segmenting units of comprehension than as strictly segmenting time and events. The reader must understand a panel in the context of the preceding panel.

Scott McCloud’s Infinite Canvas takes the idea of the panel as one segment among many in a sequence of images to its extreme. McCloud suggests a model of comics without pagination, in which panels can extend indefinitely on a single canvas. Pages are a lot like panels to McCloud: they entail the segmentation of narratological time, through the segmentation of the canvas itself. Space between two images expresses the narratological flow of time by enforcing the flow of actual reading time. Experimental comics based on this idea can branch out in every possible direction, upwards and downwards, left and right, and even into the background and the foreground using the Z-axis of the digital canvas.

Memes are just like comics when understood this way. Most commonly, they are presented as a single image in a single post. They are viewed on their own discrete (web)page, and the pretense of preceding pages and panels that contextualise the actual image currently being read is essential to the understanding of any given meme. Most interestingly, this is the case even when no previous panels exist for a particular image. For example, many postironic memes use the general style of ironic memes in order to present a stand-alone message, and often do not even reference other memes or memetic imagery in order to do so. This means that they are merely designed to look as though there were previous panels leading up to them, which would allow for a fuller understanding of their meaning. This kind of implied memelore frequently inspires people to retroactively write in the meme’s backstory.

III. Retrovirality

What happens when a comic panel is turned into a meme? First, someone might repost the image and someone else might save it to repost it elsewhere, and it might become viral. Then, others edit the comic and add components that weren’t there before. Finally, someone makes a template for the meme by cropping the comics to only the pertinent panels and inserting slots into which new components may be easily substituted. These slots act just like empty panels on a page, and may even be left empty for humorous effect.

Since comics are made up of images coupled with readily identified grammatical components, which can be swapped out with components of the same kind without problem, comic templating is trivial to do. Contrast this with memes that are deliberately designed to act like works, making modification difficult through the use of stylised fonts, textured backgrounds and overlapping images to create a collage. Although they begin as memes, they are harder to meme.

Through parody, the comic panels in the example were turned into a meme template. But the original comic would not have been considered a template until enough edits were produced that people began recognising it as a meme. The comic panels initially spread unaltered, because there was no sense among the audience that the expected mode of interaction with the comic panels was to modify them.

They became memetic through the development of variants, most of which would have been edits of edits of the original comic. Limor Shifman attempts to explain this process of viral-meme transition by distinguishing memes from virals. She defines memes as spreadable content with family resemblance, and virals as one content unit that spreads well. Virals happen because people share one version among the many possible versions of an image a lot. Memes happen because people share lots of different versions.

The templating process of comics turning viral and then memetic shows that this epidemiological model based on patterns of spread is misleading, whether it’s from the meme’s-eye-view or the agent’s-eye-view. Namely, it doesn’t explain the fact that virals and memes are frequently indistinguishable, overlapping, and behaviourally identical. By Shifman’s definition, memes are either just a higher-level group of contents made of virals, or virals are memes in waiting that haven’t been diversely parodied enough to warrant the label.

As Dan Sperber points out through an example involving a series of star shapes copied in a chain of visual Chinese whispers, most people would not be able to place memetic content in chronological order without great difficulty.

Even those already familiar with the entire chronology of a meme could not help but read additional meaning into the original, such as a sense of irony about what was to come. The subsequent panels of the long chain of sequential art have recontextualised the previous panels and given them new meaning.

Since memetic images change meaning and function throughout time, they can’t be classified based on their historical properties without rendering the classification useless for the audience. A much better way of understanding memes is as objects with embodied rules, like games.

IV. Non-Linear Sequential Art and the Memetic Bottleneck

Memes as characterised above are a form of what I call non-linear sequential art. Other examples of non-linear sequential art include any replayable games with non-linear narratives. This characterization as non-linear holds despite what skeptics may say. Amy Claussen, for instance, challenges the existence of non-linear narrative in her GDC talk called “Unpopular Opinion: All Narrative is Linear”.

A game player can go down one particular narrative pathway or another, making choices that sometimes constrain their future choices. This is called a branching narrative. As Claussen unhelpfully points out, each branch of a narrative is linear because it presents one scene after the next. Humans experience time in a linear way, with one thing happening after another. Therefore, she argues, all narrative is linear.

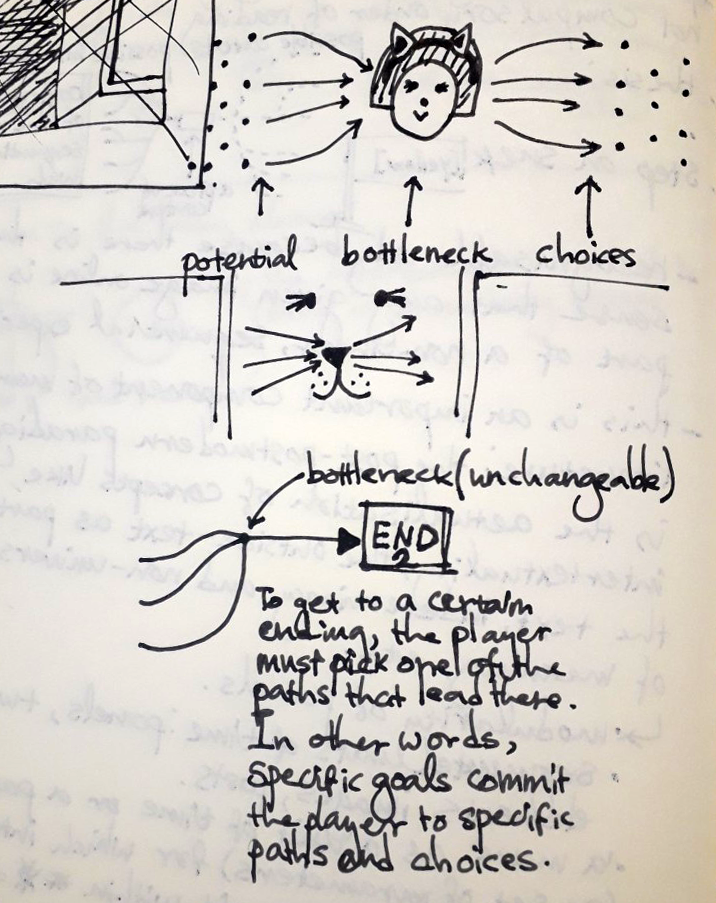

But not only are narratives experienced in linear time, they are always contextualised by the headspace of the player. This depends on the preceding experience of the player, such as a narrative branch played through before beginning the current one. When multiple narrative branches converge at one point, this is called a narrative bottleneck. This can be seen in games like Deus Ex.

Note that traditional branching narratives are different from non-linear sequential narratives. A non-linear sequential narrative is what happens when the player reloads a save file. The player’s choice of save files is about what can or can’t happen next in the game as the consequence. Inherent in this choice is the choice of what has happened in the game up to the savepoint. The choice of which save file to load is the choice of what has happened in the past, for the purpose of making certain choices possible in the future.

This is analogous to the choice between various interpretive contexts for a given instance of a meme. The audience chooses among many potential contexts and interprets the image they are currently viewing. The image constrains the potential pasts and the possible futures of the meme, bottlenecking its narrative branches. This also means that the choice to post a certain meme is the choice to evoke a particular set of scenarios in the audience’s mind, in the same way that sending someone a Civilization save file allows them to play a game with a very specific set of narratologically significant constraints.

This dynamic is one reason why it makes sense to refer to both the single instance and the totality of a family of contents as “a meme”. This is kind of like referring to both a printed set of letters on a page, as well as every spoken or written instance of that linguistic entity, as “a word”.

Like a panel in a highly networked version of the Infinite Canvas, every meme is both a potential bottleneck and a possible choice. Since the sense that every meme has a preceding meme is essential to the appreciation of memes, the memetic bottleneck works in the inverse direction of the narrative bottleneck, generating potential pasts. To choose a meme to post is to choose which game to play with the audience. More significantly, it is to choose which save file to load up: it’s scenario editing of history, conditioned on current mood.