The Meta-Ironic Era

Seong-Young HerI’ve been wrestling with the question of what makes a meme good for 3 years as a creator and memepage admin. It’s a difficult question related to, but distinct from, questions like “what makes an artwork good?” and “what makes a game good?”

The question is a pragmatic one for admins on smaller pages (under 10,000 followers by mid-2017 standards; under 1000 by 2014 standards): what content will help the page grow in the community? The answer is offered by community participants enthusiastic enough to follow small pages and give them attention, but only implicitly. Because these enthusiasts tend to have good taste, their demand for quality content exerts a pressure for better taste from the memepages. There are other strategies a small page can use to grow quickly, such as viral success with a post (either by being shared by a bigger page or by making a popular post). This frequently leads to low-literacy users following the page and locking it in a cycle of low-quality content; high-quality content (from the perspective of high-literacy users) is often esoteric and impenetrable to normies, and thus punished with lower reach. Rapid growth is dangerous for a memepage that lacks a pre-existing culture, community or an equivalent.

Medium pages (~75,000 by 2017 standards; ~10,000 by 2014 standards) are most often specialised, insular and experimental. This means that viewers need both general memetic literacy and a historical familiarity with the page. These pages sometimes form clusters with other closely associated pages which share themes and narratives, which helps them all develop. They interact with each other by collaborative content creation, sharing each other’s posts frequently, remixing each other’s contents and pooling useful techniques and ideas together. Their fanbaase often follows all of the related pages and further contributes to the community formed across these pages: they are very likely to be familiar with, or respond positively to, closely related content. Thus these pages have additional incentive to familiarise themselves with the others within their cluster. Or, they don’t remain medium for very long.

Large pages (~250,000 by 2017 standards; ~20,000 by 2014 standards) run into the opposite issue as small pages. They have enough followers that growth is less of an issue unless they want to use the reach for something other than attracting the right users for the community. But this also means that they cannot rely on the number of likes and shares on their posts to tell whether a post was good. In fact, a useful heuristic for any page beyond size 1 is to be suspicious of posts that attract more likes than usual. This almost always means it was low-quality content which caught the normies’ attention. Even large pages can get trapped in the same vicious cycle as small pages that grow so fast they lose the intuitive sense of whether a post was good or not.

A page must ride the wave of normie reach to become massive (~500,000 by 2017 standards; 50,000 by 2014 standards). The number of high-literacy users on Facebook that can find a page is restricted both by their scarcity and the algorithm. Even a page with a mixed audience will slow in its growth unless it caters to normies, who outnumber ironists in almost every case. Pages that reach this stage have little hope of establishing a high-literacy community without extreme measures. A textbook example of such a measure is Special Meme Fresh (a large page at the heart of its pagecluster) which bans anyone who tags a friend in the comments. This also helps promote post sharing instead of tagging, for extra reach.

As such, the success of a post on a page signals different things about the quality of the post depending on the context. Despite its unreliability, viral success continues to inform meme creators’ tastes. This is because the alternative of considering unquantified aspects of a meme is far more challenging. Although one of the most popular topics of discussion on the Internet, it has rarely been studied with aesthetically motivated creators in mind. Ironically, normies dominate this topic both academically (such as in virality studies and marketing) and in popular publications (often little more than listicles showcasing some “meme of the week”) and even then rely on general popularity as the conclusive metric of quality.

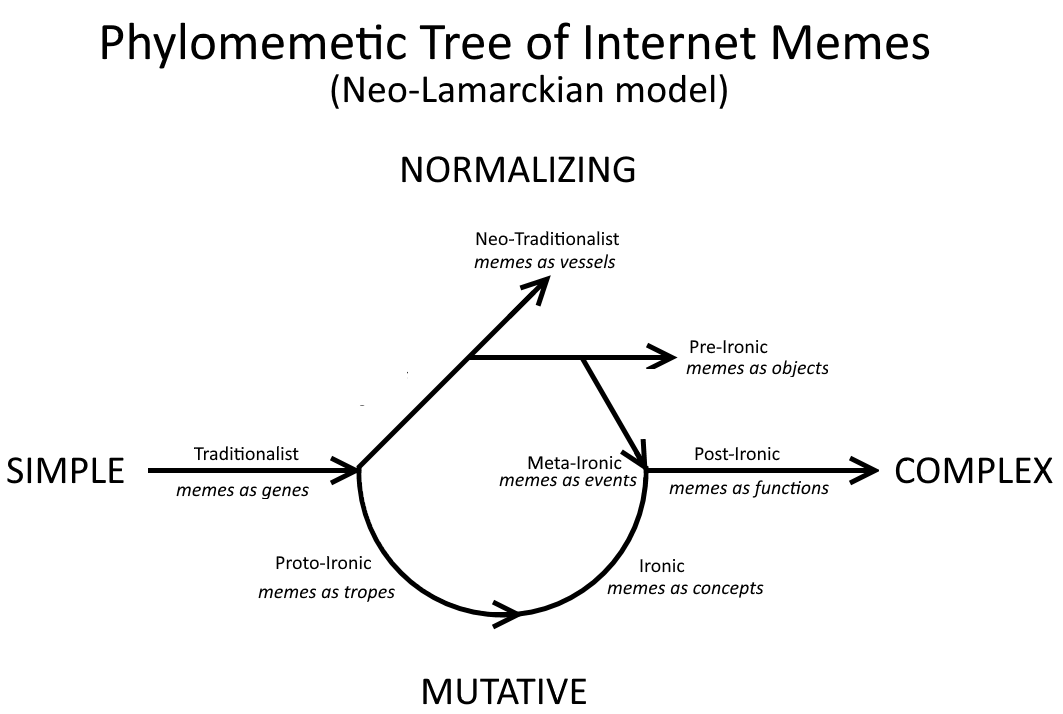

Ironists and meme researchers alike need another framework. Although the viralist framework has the advantage of an explicit and quantifiable concept of success, it is doubly harmful: its adherents find that their memes die sooner and the researchers find memetic content strangely elusive. The best place to start is by looking at some proven successes in memetic strategies, which stand out above all in their usefulness for creators. These strategies are: irony, meta-irony, and post-irony.

Irony in memes developed as the result of a clash of demographics between autists and normies.

An increasing overlap in usership between mainstream social media such as Facebook or Reddit and underground sites such as 4chan (underground in a relative sense) makes the mainstream–underground distinction less and less useful. The immigration of underground users and culture to Facebook or Reddit resulted in the need for those users to spot other users like them. This need crystallised with the evolution of joke pages (Facebook pages with humorous names which were commonly used for profile decoration purposes) into memepages. Memepages were far more engaged with their audience and interacted frequently with other memepages, compared to their predecessors which were more independent and content focused. Memepages produced content by modifying and copying pre-existing content to make original content which fit with the themes advertised by their page names. In the same way the medium sized pages of today cluster for additional content, material and reach, these early memepages clustered densely and encouraged new pages to form. Contrary to the popular belief that ironic memes were invented to “keep the normies out”, it mattered not whether they were able to participate so long as ironic memes were produced, spread and attracted new participants. In 2017, at the time of writing, most readers will find it difficult to imagine how different the dynamics of the meme community were in 2014. The sum of every memepage at the time, duplicates or no, was far smaller than a single large memepage active today.

The motivation behind ironic memepage admins is diverse and numerous. It is, however, a safe bet that the majority share a desire for a sense of community. Few things explain the community’s continued resistance to selling out by either selling the page to marketers or posting content aimed solely at growth. Part of this desire to authentically partake in the creative community comes from the anonymous cultures which precede ironic memes. In anonymous spaces, organicity and serendipity are accentuated as the community in general substitutes for the author in specific. On the one hand, the sense of serendipity was illusory (posts usually have a poster behind it who produced the post). On the other hand, an anonymous community collaborating to create content and popularise it is genuinely serendipitous. Authorship and entrenched identity on Facebook changed the dynamics of content creation and curation. While curation on anonymous imageboards happened through reposting, on Facebook a post is kept up indefinitely and redirected to through sharing. Users can subscribe to stable identities by following them. This guaranteed reach for pages that attracted an audience.

The paradigm concept of the Late Pre-Ironic Era (2001–2013) was “forced meme”. Because of the emphasis on authenticity (partly in reaction against forum spies and astroturfing or the act of deliberately engineering virality), memetic engineering was thoroughly taboo. Mere popularity did not warrant “meme status”. The big question of the era was: “is this a meme?” Is Millhouse a meme? Today’s readers will find the question odd. If it’s not a meme, it could easily become one. In contemporary meme culture, anything can be a meme. The meme culture of the future will believe that everything is already a meme.

The sense that anything can be a meme was innovated by ironists during the Early Ironic Era (2013–2015) and popularised during the Middle Ironic Era (2015–2016). Techniques often relied on the growing number of participants during this period of invention and discovery, such as in shitpics, deep fried memes and the misuse of Impact font. Content became increasingly free-form as creators experimented with alternatives to the template–subcontent framework still popular today. Notable examples to this experiment are the use of irregularly laid out stock images and word art.

The tremendous amount of experimentation and growth in size entailed the discovery of conventions, which entailed their subversion. The experimental techniques, which developed as ironic memes were popularised, gained more and more popularity, benefiting from the popularity of the former. These techniques are called meta-irony. Meta-irony is easily recognised in conventional template–subcontent memes: the meme subverts not only narrative conventions (just like ironic memes) but they also subvert structural conventions (for example, by adding distortions and lens flares). 2017 was the beginning of the Meta-Ironic Era. The coming era of post-irony is not far out of reach.