From Outrage to Dicks Out to Dead Celebrity: The Evolution of the Great Ape Harambe

Thomas Rososchansky

Harambe memes have come and gone. They lived out their natural cycle of shock, virality, ironic virality, and staleness. What is left is a residue of controversy, memes stemming from said controversy, and think pieces interpreting said memes. The think pieces, for the most part, seem fascinated with two things: the longevity of Harambe’s presence on the Internet and the surreal nature of several memes that mourn Harambe as a kind of dead celebrity or cultural icon. For better or worse, Harambe has left us with some of the most memorable images and phrases of the year. ‘R.I.P. Harambe’ no longer means ‘R.I.P. Harambe’, but rather, ‘we remember a dead fictional being based off a real dead being inside of a living meme’.

What Harambe has actually exposed about the nature of Internet memes is never talked about in these think pieces and interpretations. Harambe was not an innovative approach to memeing, but he did expose the stylistic development of mainstream memetics into the post-ironic. Taking a definition from The Philosopher’s Meme, post-ironic memes reconcile pre-ironic and ironic content, depending less on a major subversion of the joke and more on ‘numerous factors such as the history and associated nuance related to the meme’s stylistic choices’. To understand how Harambe’s development reflects mainstream media’s move toward post-irony, a brief summary of the history of Harambe-as-meme is needed, as well as a deeper examination of post-irony and meme-Harambe’s relation to it.

Harambe’s initial presence on the Internet was in the form of a scandal. A 17-year-old gorilla was shot and killed in the Cincinnati Zoo on the 28th of May in order to protect a child who had fallen into his enclosure. The final clause responsible for his death–person, politics, or power structure–was a highly disputed subject, from the parents’ irresponsibility (many demanded they be charged for failing to look after their son), the failure of the response team to use tranquilizers over guns and even the concept of keeping animals captive itself. The actions of the response team were deemed appropriate by several notable figures such as Jane Goodall, but this did not stop the political polarization caused by arguments for and against the shooting. Prominent left-wing voices like Ricky Gervais tweeted about their frustration over the event, while many on the political right praised the American gun laws that allowed the emergency response team to swiftly eliminate the threat posed by Harambe.

The social media outcry soon shifted toward an ironic nature. Memes sincerely mourning the gorilla as a victim of an unnecessary fate grew stale, with the relevant movements being overshadowed by parody; though both demanded #JusticeForHarambe, these new calls had a different intent. Early racist jokes where Harambe’s death was captioned with ‘Black Lives Matter’ became full on parodies of notably controversial cases of racial killings such as Mike Brown and Trayvon Martin. It is important to mention here that these jokes were preceded by the basic but popular racial ‘mix-ups’ that accompany the deaths of most black celebrities (think ‘RIP Mandela’ with Morgan Freeman pictured instead, except done with Harambe’s name or picture), though the irony of the joke grew more nuanced and evolved into the aforementioned BLM parody. Memes made their rounds through the Internet containing taglines like, ‘This is the picture of Harambe the media won’t show you’, painting Harambe as a college graduate or a loving father.

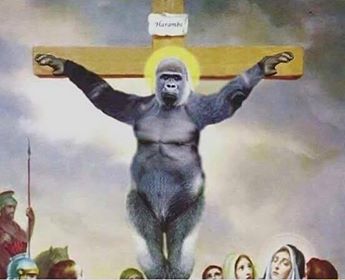

Eventually, #JusticeForHarambe’s relation to Black Lives Matter got old, finding itself limited by the boundaries of racial humour. Then, on the 4th of July, Brandon Wardell tweeted ‘Dicks out for Harambe’ (it is unknown who originally coined the phrase) and proceeded to make jokes with variations of it. The following day he released a vine with Danny Trejo in which they both said the phrase. Though ironic approaches to Harambe were nothing new, this latest ridiculous call for justice revamped the gorilla’s relevance once more–over a month after his death. The method in which ironic memes mourned Harambe was completely re-evaluated and reinvented, and his representation evolved from victim of racial or unjustified violence to fallen icon comparable to stars such as Robin Williams, David Bowie and Nelson Mandela. Harambe’s face (or a gorilla representing Harambe) reappeared on the Internet–particularly in ironic memes pages–riding shotgun with Paul Walker, having conversations with Tupac about heaven, and even in a dead celebrity mural where he stands in the centre with the sun shining behind him. Harambe was promoted to ‘lord and saviour’, with several people committing acts in his honour like swarming votes for animal names in zoos with Harambe McHarambeface.

Several think pieces were released which came to interesting conclusions about why Harambe-as-meme had such lasting power, the nature of this meme, and what this memetic spectacle meant for all future current events. With some of these requiring a large pinch of ironic salt to read, Sam Kriss tried to trace the progressing stages of Harambe’s death in his essay, ‘The Harambe variations’ (sic). Kriss examines the world’s interaction with the dead ape and the symbolism that ensued from these interactions. Once you get through various questionable (possibly ironic) interpretations like the ‘Oedipalization’ of child and gorilla or the conclusion that Harambe has transcended the metaphysical to become the lens with which we see the world, Kriss touches upon a particularly compelling assessment of the nature of Harambe memes.

Interpreting a different essay by Brian Feldman, Kriss states that Feldman ‘situates the death of Harambe within a network of other memes… Signifiers relate only and always to other signifiers, and Harambe has become a metasignifier, taking on a Barthesian dimension of myth.’ Later on Kriss revises his ‘metasignifier’ term and refers to Feldman’s conception of Harambe as ‘the ape as empty signifier’ (or are these two the same thing, yet different?). What is particularly noteworthy is the word ‘empty’ replacing the prefix ‘meta’. An empty signifier (also known as a floating signifier) has no referent because its signified is problematic, ambiguous or too lost in plurality for a single definitive meaning to be set. The referent, which supposedly should be the dead gorilla whose essence has become a sensation, cannot truly be Harambe as nothing in the signifier logically brings us back to the same gorilla without some addition or subversion. While it is most likely that Kriss is crediting Feldman’s words with a nuance that is not there, this idea takes us back to our central point. Perhaps what Kriss is referring to is the ‘rational’ signifier that is missing from the most recent Harambe jokes: the connecting language between the death of a gorilla and his sudden and unexpected image as a celebrity, musician and political revolutionary. What is seen by Kriss and Feldman (in Feldman’s words) as ‘fairly standard Internet non-sequitur nonsense humor’ is the post-ironic nature which Feldman does not recognise and Kriss does all but mention: a joke which does not explain itself, expecting the history and nuance of a meme’s stylistic choices to stand in the place of reason, which people would normally seek in its peculiar narrative instead.

If we observe the quadrant of ironic memes from the same glossary we used to define post-ironic memes, we can see that the Harambe meme is structurally but not narratologically subversive and that it acts like a meme while it does (or might) not look like one. The narrative remains the same: ‘R.I.P. Harambe’, but now the gorilla is sat next to recently dead musicians, actors and historical figures; he is driving Paul Walker’s car in the final scene of Fast and Furious 7; he is being mourned by George Costanza with Kanye West lyrics originally directed at Michael Jackson. The pre-ironic memes were prevalent during the sincere outcries for justice, the ironic memes directly mocked this behaviour in social media and the post-ironic memes returned to the ‘mourning’ period, but with a mystical and reverent twist. As the quadrant says, post-ironic memes are ‘pre-ironic memes stylistically subverted’. The mere image of Harambe now stands on the foundations of the history of his own aftermath. The meme’s progression through layers of irony is a simple one: with straightforward outcry as thesis and a mockery of said outcry as antithesis, the synthesis is a mourning which reconciles both, perpetuating the sincere tragedy of Harambe while making fun of social media’s approach to fallen heroes.

The post-ironic Harambe serves multiple functions, fortifying the enigmatic ‘meaning’ that would otherwise make a meme accessible to normies. There are three notable things at play in the post-ironic stage of this meme: we see Harambe as a parody of dead celebrities and therefore of those who mourn dead celebrities in memes. We see the grief over Harambe as the ultimate form of sarcasm over a situation (the shooting of a gorilla) which some people found menial and clear-cut during its unfolding. And, finally, the ambiguous reason as to why his death is actually lamented drives a comedy of absurdity into the meme itself. Our irrational sympathy for Harambe is a nod to the irrationality of life itself, how we too are subject to and coerced by forces we cannot grasp. The humour in deriving such a tragic notion from such a random event is only the more appropriate in this absurdist context. The post-ironic Harambe is nothing like the original Harambe; what began as an outlet for facts about western lowland gorillas and arguments about who was to blame was transformed into a eulogistic set of jokes, constantly revising and updating Harambe’s personality as one of the fallen greats of our time.

As a statement about how we mourn our heroes, there is much to absorb from the post-irony that has overtaken Harambe. The sudden and fictional achievements given to the gorilla reflect our tendency to fill our memories of recently dead icons with nothing but merit and fondness, a common reaction to death that serves the purpose of immortalising the deceased. Meanwhile the sentimentality toward Harambe works as a different component of this satire, as a reminder that celebrities tend to receive affection and empathy from people who do not truly know them. As communications improved and brought us access to something as widespread as the Internet, we turned artists into ‘personalised’ figures for their audience, each observer discovering varying amounts of information about the artist’s personal or professional life. While the Internet has given us the gift of multiple perspectives, both qualified and unqualified, when engaging with facts, it has also augmented the facts themselves at an explosive rate. Granting people privacy is no longer a popular virtue nowadays. Whereas in the past it was difficult to stay off the tabloids as a celebrity, today it is nearly impossible. The artist is exposed for everyone to learn about in varying degrees, and so traditional ways in which we react to death are now customs we grant to people we have never met. People who have touched our lives without even knowing it are memorialised falsely, based on feelings and impressions from strangers who have a distorted vision of them through their own online lens. The great thing about Harambe as a post-ironic joke is that he functions the same exact way as these inappropriately adored celebrities. To say ‘R.I.P. David Bowie’ is to evoke his musical and cinematic history and achievements, in the same way that saying ‘R.I.P. Harambe’ evokes the real and invented history and achievements attributed to him after his death.

Part of the charm of post-ironic memes is that they appeal to both the regular memer and the normie (an outsider to meme culture). This is accomplished by what Matthew Collins terms in his article the ‘who cares?’ attitude. The phrase ‘who cares?’ here is referring to the clarity in the irony of a post-ironic work. Collins says ‘irony and sincerity are now just sitting side by side–they’re inexorably linked.’ So those who laugh at the meme’s ironic implications laugh alongside normies who enjoy its sincere attempts at being silly or weird. Harambe therefore entices newcomers while moving its acquainted audience forward, made accessible through a cryptic and shadowy definitive purpose. A good example of how this works can be observed in the phrase ‘Dicks out for Harambe’ (an early example of post-ironic Harambe) utilising an expletive to delve into ambiguity. The narrative is not subverted and the mourning element is still there, but the style has gone from a sincere or ironic disgust of unjust killings to an absurd request in remembrance of the gorilla. The ‘unjust’ essence is no longer present, but the post-ironic joke depends on the viewer’s knowledge of previous chants of injustice to laugh at this new state of grieving. On the one hand, ironic memers will enjoy the latest subversion of the way in which we mourn Harambe, while also recognising ‘dicks out’ as a satire of the self-indulgent way in which people feel the need to voice their opinions about everything (such as the shooting of a gorilla), but who will not physically do anything to improve the situation presented to them. On the other hand, the bizarre aspect of exposing one’s penis to pay homage to a dead gorilla will also appeal to the normies. It is through this nature of simultaneously being devoid of and packed with implicit meaning that made Harambe harmoniously thrive in ironic and normie circles for so long.

One constant issue that gets brought up, however, is the question of whether or not Harambe is a racist meme. Meme pages on Facebook like Lettuce Dog have argued that not only does the meme de-centre and trivialise recent black victims of police brutality, but it also perpetuates ‘the myth of black sub-personhood through ironic memorial of a dead Gorilla’. The evidence people turn to when backing this argument is the undeniable amount of racist memes made with Harambe, believing that the post-ironic Harambe that is memorialised must be intrinsically linked to his past incarnation, continuing to mock Black Lives Matter and black victims of police killings implicitly. While Harambe will inevitably signify racism through its implicit history, it also will not. The post-ironic Harambe is and is not racist in the same way it is and is not sincere. Its image doubtlessly signifies its history as a racist meme, but at the surface Harambe is being compared to icons indifferent to their race and treated as a Christ-like figure. The meme’s racist and non-racist natures are reconciled in the ambiguity of post-irony, that ‘who cares?’ attitude which defends and justifies the meme against the aforementioned arguments. It does not perpetuate injustice by its lack of taking an ethical stance, instead it promotes itself as a shared experience or cause that has overcome the notion of meaning before solidarity.

As Harambe has become a melting pot of meaning, people’s disdain for the meme will only fuel the meme-making fire to redefine Harambe with a rebellious essence against his contenders. There is no doubt that requests to put a stop to Harambe memes can only enrich the gorilla as a signifier, spurring people to continue spreading the meme in order to troll any pleas for its end (it is how this inevitably and immediately led to this). A post-ironic nature means that the meme has already become stale in some parts of the Internet while it still flourishes in others. Harambe has become such a well-known motif that even the dead celebrity aspect has started to trail away as an unnecessary characteristic. Anything gorilla-related at this point will accomplish the same signifying purposes its antecedents had, from abstract images of apes to dance videos of computer-animated gorillas (some of these will drop the mourning narrative altogether and become meta-ironic memes, jokes that are structurally and narratologically subversive). While the joke appears to be so random and/or minimalist that it comes off as a parody of post-irony itself, it has definitely exposed how far the world’s embrace of post-ironic memes has come. Standard narratives will be met with disenchantment and incredulity, be it ones presented by the media or existing narratives, perceived as long-standing beliefs within the incredulous audience. Harambe memes will meet the same mortality of staleness that all previous memes have met before it, but there is no telling what this blurring of irony and sincerity will do to our perception of future world events and reality itself.