Hotline Miami and player complicity

Mike M."Do you like hurting other people?"

I.

Hotline Miami is top-down pixel-graphics game set in 1980s Miami. The setting and graphics create a vibrant and psychedelic environment which is further energised by the fantastic electro-disco soundtrack. The player controls a character that fans of the game have named 'Jacket'. The game begins in Jacket's apartment when he finds a message on his answering phone that tells him about a package that has been delivered. Outside the apartment is a box containing a mask and an address with some vaguely-worded instructions. From there, the player gets in Jacket's car and drives to the address, finding it full of armed enemies. Jacket dons the mask and proceeds to infiltrate the building, violently contending with the people inside. Each stage follows this same situation: a closed space that Jacket must clear by defeating every enemy on every floor of the building before leaving and being given a performance grade.

To state it lightly, Hotline Miami is an incredibly violent game. When enemies are dispatched (which can be done with a variety of weapons scattered around the stages), their deaths are accompanied by vast and improbable fountains of blood splattering over the screen. Downed foes can even be finished off with grizzly 'coup de grace' executions. All of the killing is rewarded in the form of a grade and a score, with a greater score awarded for consecutive and/or especially gruesome kills. Levels are not completed until every last enemy is killed.

The action is fast and furious, with kill streaks being the best way to proceed through the level, violently bashing, slashing, stabbing and shooting your way through the stages. If at any time Jacket dies, the game allows you to push a button to instantly start at the beginning of the level, the awesome music still thumping in your ears and new weapons scattered around. You might be forgiven for thinking that this is just a typical top-down arcade game that rewards players for their reflexes and aggression, however what distinguishes Hotline Miami is it's use of backtracking.

II.

'Backtracking' in videogames refers to forcing the player to walk back through areas of the game they have already visited. It carries a lot of negative connotations as the mechanic is usually employed by lazy developers in order to pad-out the length of their game or to re-use game environments in order to cut down on production costs. Where 'backtracking' is most often used as a crutch to support the rest of the gameplay, Hotline Miami has the bravery to turn backtracking into a mechanic.

The player is almost certainly going to die multiple times on attempting each stage, forcing them to revisit the same areas over and over again, witnessing their own gruesome demise each time. After seeing so much blood, aggression and their own death so many times, you'd expect the player to become somewhat numb to the brutality, and this definitely happens.

However, after Jacket has successfully slain the final enemy in each stage the music grinds to an uneasy halt, replaced by an unnerving whine. Instead of focusing on slaughtering faceless aggressors, the player now navigates back out of the confined space they have just fought their way into, and is forced to confront the awful carnage they created on the way in. These backtracking sections provide what most videogames don't: a forced confrontation with the consequences of your own ultraviolence. Nobody gets back up to fight you, nobody even moralises about how terrible you are: you just walk past the battered corpses and bloodsoaked floors all the way back to your car while the music whinges at you. In stark contrast to the extreme violence and the despondency to it that the player is likely experiencing, the player is now explicitly numbed (music is gone, action suspended, camera becomes steadier etc) and asked to step back through what they did, almost as if travelling back through time and witnessing themself through a different pair of eyes.

III.

The uneasiness is catalysed by the cutscenes that occur between missions where the player learns that Jacket's motivation for killing is rather... nebulous. Jacket never talks and simply accepts the rewards he is offered after successfully carrying out his missions (rewards that are often as anodyne as free pizza). Other characters actually become hostile to Jacket, berating him and refusing to reward him later in the game, despite him still carrying out the missions he receives through his answering machine. The game begins to directly criticise Jacket and his lack of resistance to the killing, openly questioning him as to why he is complying with the anonymous voices in his answering machine, with the point perhaps being made that the player themselves are displaying the same dispassionate compliance by continuing to play the game. Jacket isn't getting any rewards any more yet he continues to kill... what exactly is the player getting out of this?

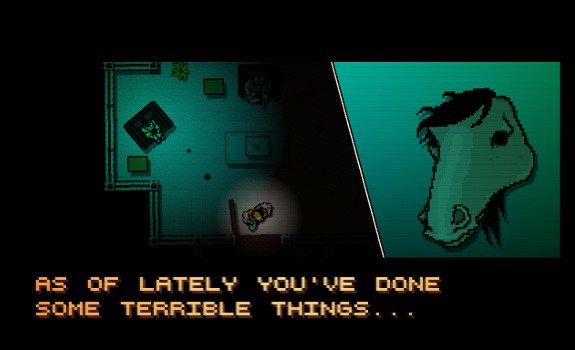

This interrogative is made most clear early on in the game when the game characters intentionally ask Jacket several questions that seem to break the fourth wall, in dialogues that could well be directly addressing the player. These questions "Do you like hurting other people?" and "Where are you right now?", go unanswered as the player and Jacket have no way of responding to their interrogators. The characters who ask these questions all seem to have animal faces similar to the masks that Jacket wears before starting his rampages, and as such some fans have even theorised that they are projections of his personality, the different animals representing different aspects of him. The question being rather unsubtly asked is "What nature of beast is man?", as none of the animal personas are able to fully identify with or relate to Jacket (in fact, the owl-faced character seems to detest him), and Jacket makes no attempt to answer their probing questions, or even dialogue with them at all.

IV.

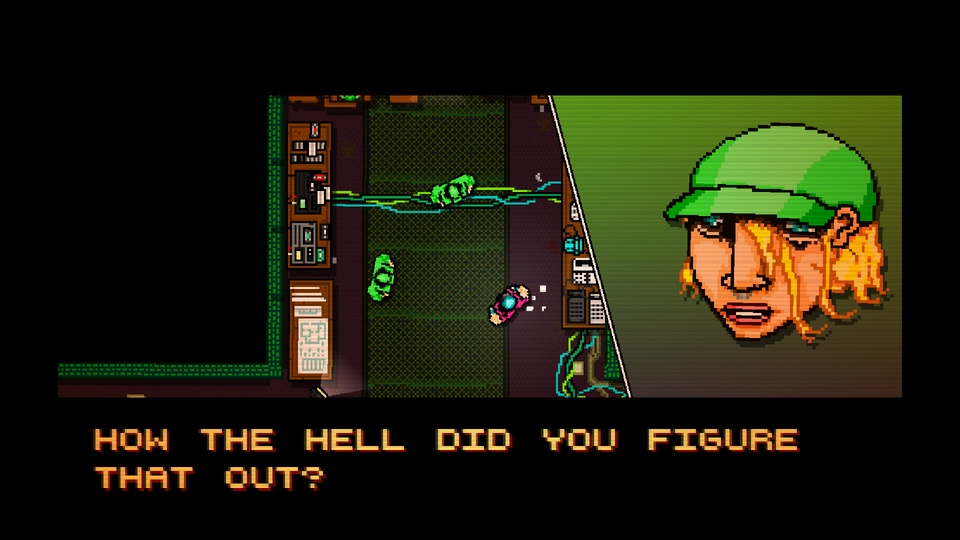

After the end of the game and after the credits, the player is given the opportunity to play several 'bonus' chapters as another character. Instead of the mask wearing Jacket, the player now controls the motorcycle helmet wearing 'Biker' who appears as an antagonist to Jacket in the previous chapters. Playing through Biker's chapters provides an alternate interpretation of the events of the game. In contrast to the silent Jacket, Biker barks lots of questions as he interrogates other characters and tries to find out how he can stop the messages appearing on his answering phone. It is interesting to note that Biker's section of the game is the only part where you have the option of leaving people alive.

The silent Jacket asks no questions and as such ends up spiralling into ever more violent confrontations. Biker, who is consistently running his mouth off and asking questions about who he is being ordered to kill (and why), is able to break away from the violence and stop the madness. Jacket wears many animal masks and kills without question, he eventually ends up killing even without instruction embarking on a violent rampage against the mafia who have killed his girlfriend. Jacket has become a beast, the animalistic masks mimicking his departure from humanity and towards the violence and chaos of the predatory world. Biker on the other hand takes off his motorcycle helmet and engages in dialogues with other characters. While he is still an ultraviolent killer at the beginning, his quest to find answers ultimately leads him to be able to conclude the game somewhat peacefully (although this is optional). Through embracing his uniquely human abilities of speech and intellect, Biker is able to indirectly question the morality of his actions and confront his own motivations and ultimately choose his own outcome.

The violence that occurs within the game is not just an obstacle to progress, in fact the player contending with violence and being willing to take part in it IS the narrative, hence one might call it 'narrative violence'. This kind of narrative relies on the violence and the player/audiences interaction with violence on a personal level to actually tell the story and convey the message. Violence isn't just part of the plot... somehow it IS the plot, and it uses it's mechanics to advance that plot.

V.

The wanky phrase that gets used a lot in videogame criticism (and usually used in the pejorative) is 'ludo-narrative dissonance', where a game's mechanics and story don't fit together. Hotline Miami is an example of exactly the oppsite; ludo-narrative consonance? The mechanics of the game are integral to telling the story and exploring the themes in a way that couldn't be achieved in the same way in other media (film and fiction are more passive and hence couldn't reinforce the idea of complicity in the same way).

The most obvious theme is turning a critical eye towards violence in popular media, but Hotline Miami also contains a more subtle question about complicity. Not just player complicity in the violence of videogames, but general compliance of society. We get told what to do and then... what? We just do it? Really? Hotline Miami gave you the tools and the space to act out your brutality and then... you did it? Really? Wow.

"Well, I'd like to not have to kill, but I don't have a choice: there's only one way to play the game! Is the violence not the intention of the game developer and thus ultimately not my responsibility?" You might protest, and miss the point.

You're right that the game forces you to kill, but nobody forced you to play the game.