The Ironic Normie

Thomas RososchanskyOn some parts of the Internet the term ‘normie’ is used to define anyone who does not fully comprehend the humour and language of certain communities. A normie is usually seen as someone who has a social life outside of the Internet, and who does not know, or care, about its obscure customs. In this particular case, the term is as much an accusation as a label, expressing disdain toward anyone who is unaware of the growing community of Ironic memes. Though a normie used to simply be a person who was able to thrive in the outside world, the developing elitism in Ironic memes tainted the word to being a threat to Ironic humour. As the term was used more and more for people who do not comprehend Ironic memes, the dichotomy between those who ‘got it’ and those who didn’t was fortified and popularised. However, this contempt for normies did not stop them from finding out about Ironic memes and, conversely, finding out about Ironic memes did not rid the normies of their label. This essay explores how a middle ground is developing between normies and non-normies, as well as what implications this might have.

The title ‘normie’ as the marker for a nonconformist of memes is not enough, and by that I mean the simplistic binary of ‘meme aware’ versus ‘normie’ has now gained too many layers to remain as it is. As Ironic memes slowly crept into normie circles, one of two things happened: Either the number of normies decreased significantly as the awareness of Ironic memes grew, or (the more feasible explanation), the idea of what constitutes a normie expanded and began penetrating Ironic meme culture. The reason I state the latter is more plausible is because simply being aware of Ironic meme culture did not change the attitudes and normie-like approaches to memes, what changed was merely the content. The word ‘normie’ has obvious connotations to ‘normal’, which became paradoxical as Ironic meme culture started prevailing in normal communities and circles. The normies, therefore, are unchanged in their ways, treading on land that is either dying or being left behind but nevertheless still a part of Ironic meme culture.

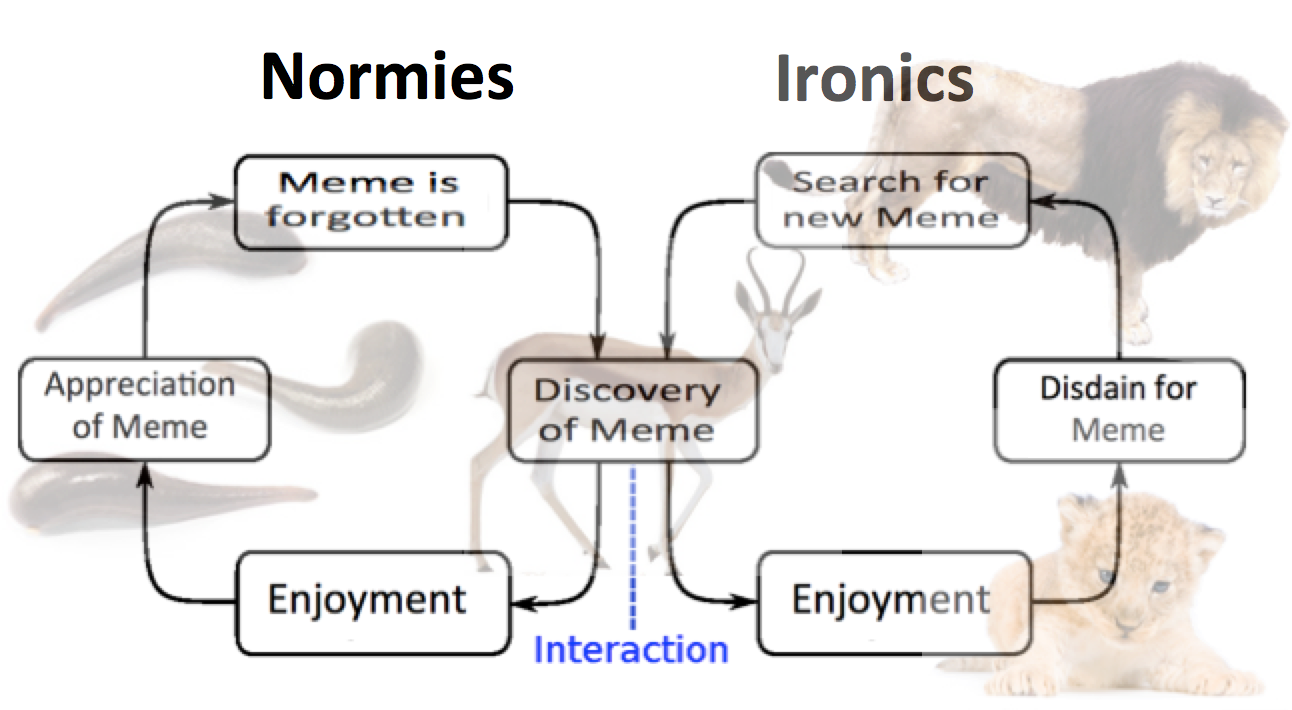

The Ironic meme culture has dispersed into immensely different levels of knowledge over trending memes. From these levels, we can mark two different mentalities that are polar opposites. The first, which demarcates the less knowledgeable, is the conclusive. This mentality is normie-based and limits one’s ability (or willingness) to move further into their knowledge of meme culture. Conclusive users are presumptive and naïve. They do not seek out but allow the jokes and formats to reach them through popularity or word of mouth. The conclusive user believes what they see is at its finalised stage of humour, repeating the joke to the point where it becomes stale and moving on only when they are presented with something new. The second type of mentality is what pushes the Ironic meme culture to evolve, sometimes into increasingly obscure areas as well: the inconclusive. The most keen to find new content, the inconclusive user’s grasp of general meme history shows their awareness of how memes are mobile and hard to claim. With this acknowledgment comes their proneness to dismiss a meme as canon after a certain amount of time, already paranoid about how much contact the meme may have with normie circles which, in turn, pushes the user to find newer content.

Although introduced to Ironic meme culture, the normie does not decline from social activity; the normie does not sink into his or her chair with a bag of Doritos in reach; the normie does not lose friends (because their tendencies remain the same and they, as the conclusive users, do not seek out memes instead of focusing on their real lives). In other words, the definition of normie remains the same, though the user is now aware of ironic content. A great reason the tendencies don’t change is due to the ironic content being presented in normie pages on Facebook, which usually specialise in pre-Ironic memes or clickbait news. Because the ironic content is delivered in the same medium as pre-ironic content, the mentality of conclusiveness is uncorrupted, giving the normie no reason to seek content further than where they are already given it. Another source from which the normie comes across ironic content is through a popular Weird Facebook page that has developed an enormous following. This still does not affect conclusive tendencies because the page needed to be popular enough for the normie to discover without ‘seeking’ and, additionally, the growing numbers usually force the page to take a less obscure and more relatable approach to humour, which does not encourage any effort in understanding the joke’s meaning either.

Although introduced to Ironic meme culture, the normie does not decline from social activity; the normie does not sink into his or her chair with a bag of Doritos in reach; the normie does not lose friends (because their tendencies remain the same and they, as the conclusive users, do not seek out memes instead of focusing on their real lives). In other words, the definition of normie remains the same, though the user is now aware of ironic content. A great reason the tendencies don’t change is due to the ironic content being presented in normie pages on Facebook, which usually specialise in pre-Ironic memes or clickbait news. Because the ironic content is delivered in the same medium as pre-ironic content, the mentality of conclusiveness is uncorrupted, giving the normie no reason to seek content further than where they are already given it. Another source from which the normie comes across ironic content is through a popular Weird Facebook page that has developed an enormous following. This still does not affect conclusive tendencies because the page needed to be popular enough for the normie to discover without ‘seeking’ and, additionally, the growing numbers usually force the page to take a less obscure and more relatable approach to humour, which does not encourage any effort in understanding the joke’s meaning either.

We know the sources, but I have not yet reflected upon the motivations that lead to those sources. The main explanation for this occurrence comes under the notion of epistemic luck. As there are several right and wrong ways in which one can come to a true belief, the normie reaches the enjoyment of the meme in several different ways that are wrong enough to maintain the user’s awareness at a normie level. For example: there may be a popularity factor. In the same sense where one might expect a song in the charts to attract more listeners through its reputation, the page dispensing Ironic memes has garnered enough numbers to assure a normie of its quality through quantity of followers. The normie enjoys the meme because they are aware of its general response being positive, regardless of whether or not they understand the joke themselves. There is strength in numbers, the strength of reassurance and credibility, leading to a normie following the masses toward his feed of comedic entertainment. Another approach of epistemic luck could be through a “lucky guess” or the normie laughing for the wrong reasons. The normie is shown something funny that they do not comprehend fully, but at the lowest level of meaning there is still some humour to be dispensed. Therefore the normie, by chance, is amused by the same memes that a non-normie likes, the only difference is the normie’s grasp of the meme is less learned, therefore finding the meme funny or amusing through less or entirely different motives. Furthermore, the normie might identify with Ironic memes through wishful thinking. The normie is shown something that they do not understand in message, but they understand in medium. In other words, there is no real gauging of the meme itself other than the knowledge that it is meant to be ironic. This could be enough to justify the normie’s amusement from the meme, the knowledge that there is something deep in the meme’s context as ironic. It could also be more than just one reason, of course. The normie is not limited to simply discovering these in one way; they could be driven by both a sense of the meme’s popularity and its status as ironic, or they could know the meme’s reputation and therefore be driven to enjoying some part of its humour.

My reason for beginning the essay with the statement that ‘normie’ wasn’t enough comes with the following argument: due to the pages packed with pre-ironic content being some of the biggest deliverers of ironic content to normies, the level of the viewers’ awareness is not clear. A normie is not expected to enjoy ironic humour but they do while continuing to misunderstand it; this forms a bridge between the two worlds of memedom. When a meme is posted, there is always an inevitable ‘death of the artist’, in that the meme will only hold as much significance as its audience gives it. We have learned before that, beyond Ironic memes, we find meta-ironic subversions (stylistically and narratologically liberal) and post-ironic subversions (stylistically conservative and narratologically liberal) of memes. However, when a meme is posted in normie circles, the only context comes from the page that posted it (especially with normie pages scarcely citing any sources), meaning that the meta-ironic or post-ironic definers are lost under the general clause of ‘ironic’, simplifying every content’s humour as surreal comedy. In this middle branch of being aware of different content but misreading and blurring the content’s original intent, the normies find themselves in a deeper area of meme-knowledge that isn’t fully realised; they become ‘ironic normies’.

This intellectual hegemony taints the individual merits of the meme. As the more vocal readings take the lead, the content becomes generally accepted to have less meaning for more people. Any obscure circle of well-read users who find a meme shared with normies will instantly become irate and disdain the use of the meme either completely or in its original context. As the number of ‘ironic normies’ grows, the content is received faster by them and, consequently, abandoned faster by non-normies, causing an exponential rise in the making of Ironic memes.